The first time I started paying attention to Vanar was not because of a feature, or a narrative, or a benchmark.

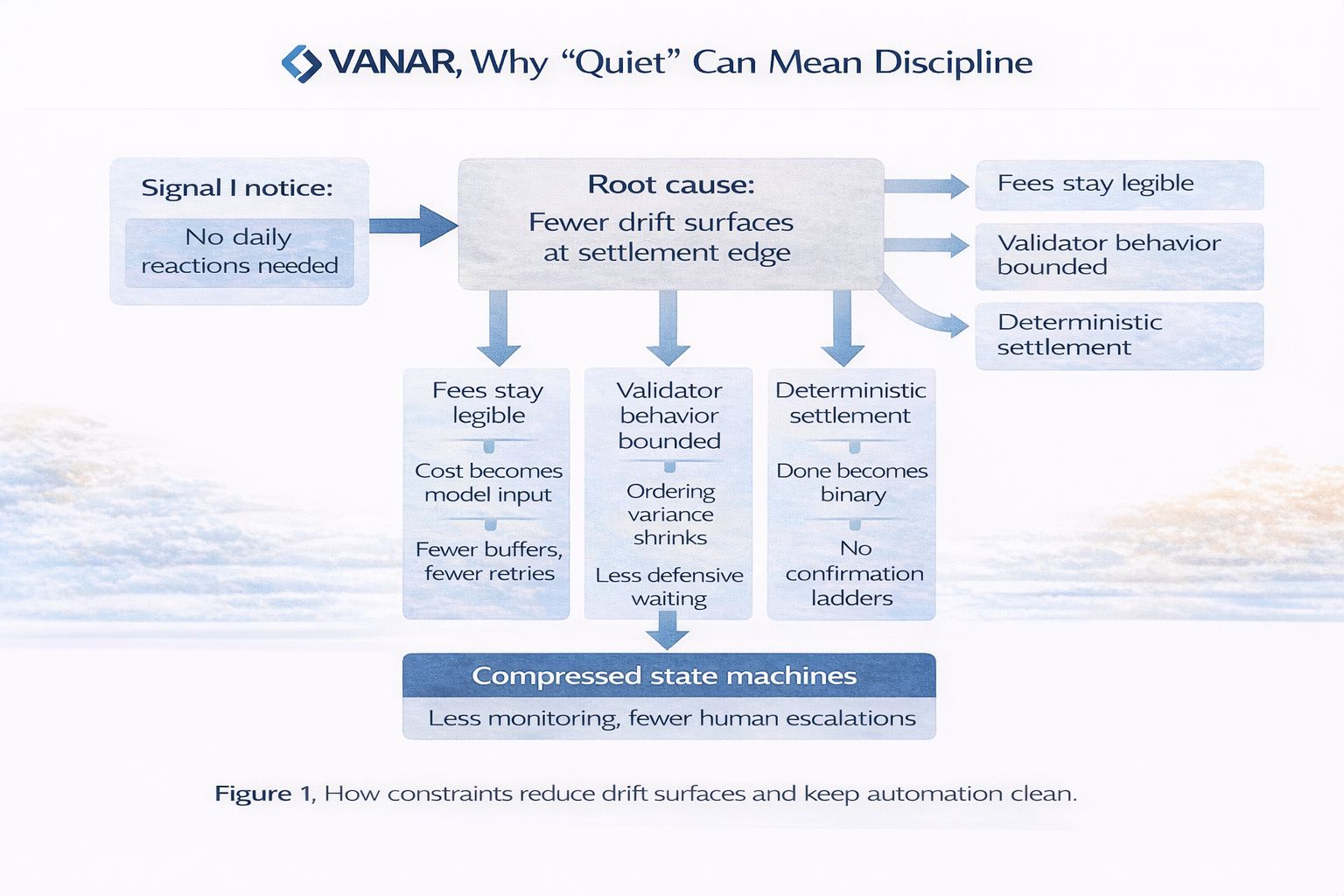

It was because I noticed I had nothing to react to.

No sudden fee behavior that forced me to reprice a workflow. No “just wait longer” advice when settlement got awkward. No subtle drift that made me add another confirmation step “just to be safe”.

It sounds like a small thing, but after enough years operating systems that run daily, the absence of that constant micro-adjustment is a signal. A chain can look stable because it is quiet. Or it can be quiet because it has decided what it refuses to allow.

Vanar reads like the second.

I did not arrive at that conclusion from marketing claims. I arrived at it from the way Vanar frames its infrastructure around constraint, the kind of constraint that prevents certain failure modes from ever becoming normal. The longer a system runs, the more that matters, because real fragility rarely announces itself as an outage. It appears as an extra step someone adds later.

A small buffer in a budget check. A retry branch that becomes permanent. A monitoring alert that turns into a daily ritual.

Those are not features. Those are symptoms.

What makes this relevant to Vanar is that Vanar’s design choices seem to attack the exact sources that create those symptoms, fee behavior, validator discretion, and settlement finality. Not as isolated “advantages”, but as a single story about reducing the number of ways a workflow can quietly become conditional.

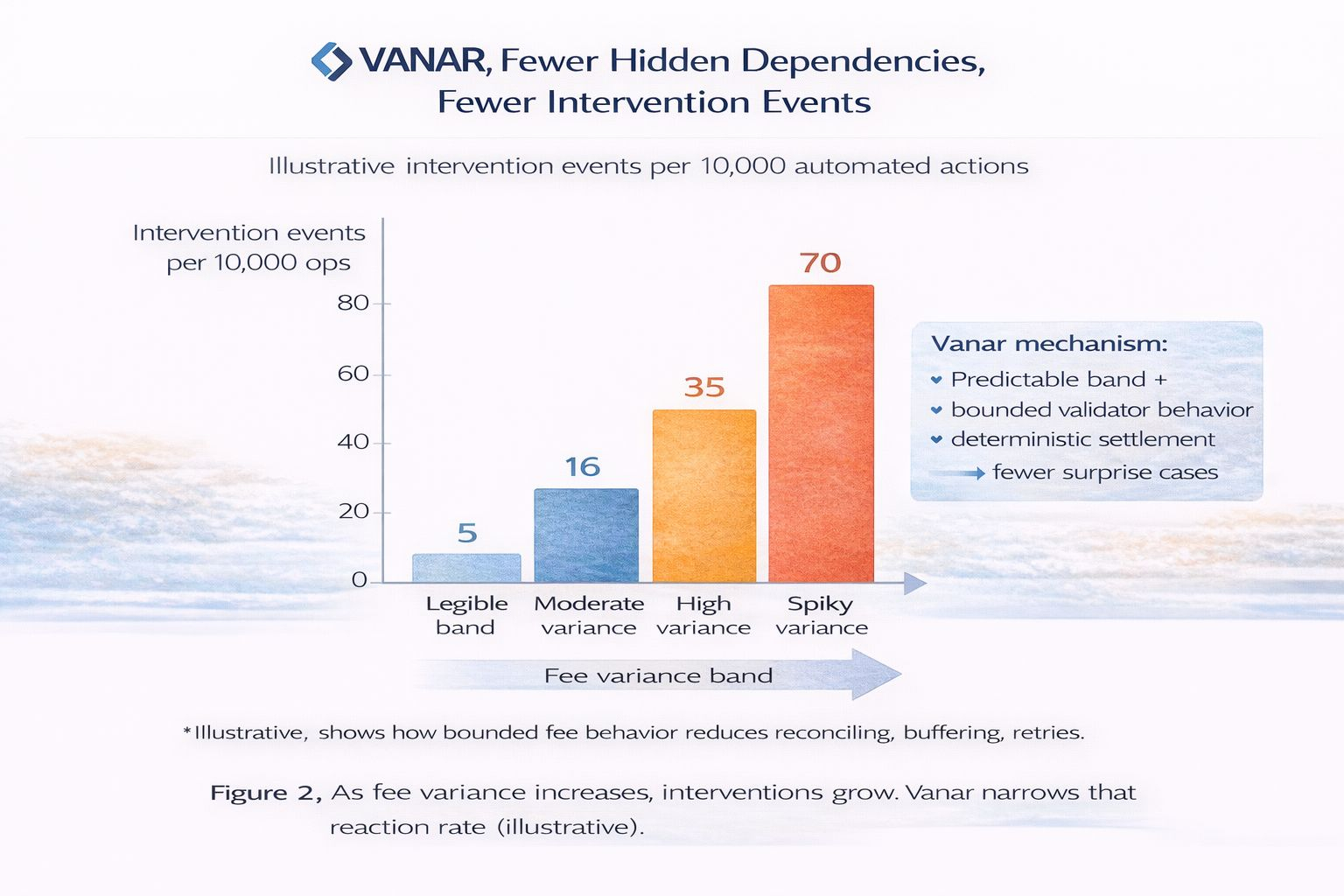

I learned the hard way that “fees” are not a price in production automation. They are a contract.

When cost is legible, you can model it. You can write clean logic. You can treat completion as binary. When cost is not legible, you stop building product logic and you start building uncertainty management.

And the moment you start estimating, you are already paying interest.

You add bounds. Then tolerances. Then guardrails. Then escalation paths.

What caught my eye with Vanar is that it does not talk about predictable fees like a convenience. It treats fee behavior like something upstream systems must be able to assume. That single stance changes how an operator designs around the chain. If cost stays inside a controlled band, automation does not need to grow a second brain just to decide whether to execute.

But fee predictability alone does not hold if the rest of the system can still drift under stress.

This is where Vanar’s stance feels coherent instead of cosmetic.

Validator behavior is the second place where systems quietly force humans back into the loop. In many networks, validators are “free” in the sense that incentives are expected to shape behavior dynamically. On paper, this is elegant. In day to day operation, it means ordering and timing can vary enough that downstream systems stop treating them as stable meaning.

And once ordering becomes soft, workflows become defensive.

You wait longer. You confirm more. You design around worst-case paths instead of expected paths.

Vanar appears to narrow that freedom envelope earlier. It reduces how far behavior is allowed to stretch under pressure. That does not make it magically perfect. It makes it easier to assume repeatability. And repeatability is what automation needs if you do not want a human to babysit edge cases.

The third piece is the one that decides whether the story is real, settlement finality.

The reason probabilistic finality creates so much hidden labor is not fear. It is structure.

If “done” is a gradient, every layer above invents its own threshold. One service waits 10 confirmations. Another waits 20. A third triggers on “most likely final” and compensates later.

Nothing is broken, but nothing is clean. And reconciliation becomes a permanent job.

Vanar’s interesting bet is that settlement should behave like a boundary, not a slope. Once something is finalized, downstream systems should be able to treat it as a binary event, committed or not. That is not a headline metric. That is an operational relief.

Because when “done” becomes binary, the state machine compresses.

Fewer branches. Fewer retries. Fewer exception paths that require interpretation.

In day to day operation, I trust compressed state machines more, because they are easier to audit, easier to reason about, and easier to keep stable under automation.

This is why I do not describe Vanar as “quiet” in the way people describe inactive ecosystems. I read Vanar’s quiet as discipline.

It is a refusal to outsource ambiguity upward. It is a refusal to let drift turn into normal operation. It is a refusal to rely on human vigilance as part of the design.

That refusal has costs, and they are not imaginary.

A chain that commits to legibility and bounded behavior will feel restrictive to builders who want maximum optionality. Certain composability patterns thrive on freedom, on emergent behavior, on the ability to wire anything into anything. Vanar’s stance implies those behaviors should be introduced carefully, if at all, because emergent behavior at the settlement edge is exactly where long-running automation gets hurt.

The market usually rewards the opposite.

It rewards the chains that look alive because something is always changing. It rewards the ecosystems where flexibility is framed as strength.

But if you have operated systems long enough, you start to recognize the darker version of “alive”.

Alive can mean unstable. Alive can mean you are carrying a human correction layer you do not want to admit exists. Alive can mean your product works because you are always watching it.

Vanar’s bet is that serious systems will eventually run in environments where nobody is watching closely enough, and that infrastructure should behave the same way anyway.

Only late in that story does it make sense to mention VANRY.

If Vanar’s design is genuinely about constrained settlement, then the token is not the thesis. It is the coupling mechanism, the way participation, usage cost, and coordination are paid for inside a system that is trying to keep behavior legible over time. VANRY matters if and only if the underlying “contract” stays stable enough that automation can lean on it without building a paranoia layer around it.

I do not know whether the market will reward this kind of discipline.

But I know what it feels like when systems slowly demand more attention just to stay upright. They do not fail loudly. They just become expensive to trust.

Vanar is one of the few designs that seems to treat that as the main problem.

Not how to move faster. How to stay legible after month six, when nobody is excited anymore, and the only thing that matters is whether your system still behaves like the contract you thought you deployed.

That is the version of infrastructure I have started valuing, and it is why I keep coming back to Vanar.