Most public blockchains were built around universal transparency: every balance change, counterparty link, and position history is visible by default. That works for open settlement, but regulated finance has a different baseline confidentiality for client data and strategies, plus the ability to prove compliance on demand. When everything is public, institutions end up choosing between leaking sensitive information (front-running risk, exposure mapping, relationship disclosure) or moving critical workflows off-chain where oversight becomes fragmented. Add-on privacy layers can help, but they often introduce new trust and integration boundaries: separate proving systems, different failure modes, and operational complexity that compliance teams must sign off on.

A transparent ledger is like conducting every audit by publishing everyone’s bank statements on a bulletin board and then asking the market to “ignore” the sensitive parts.

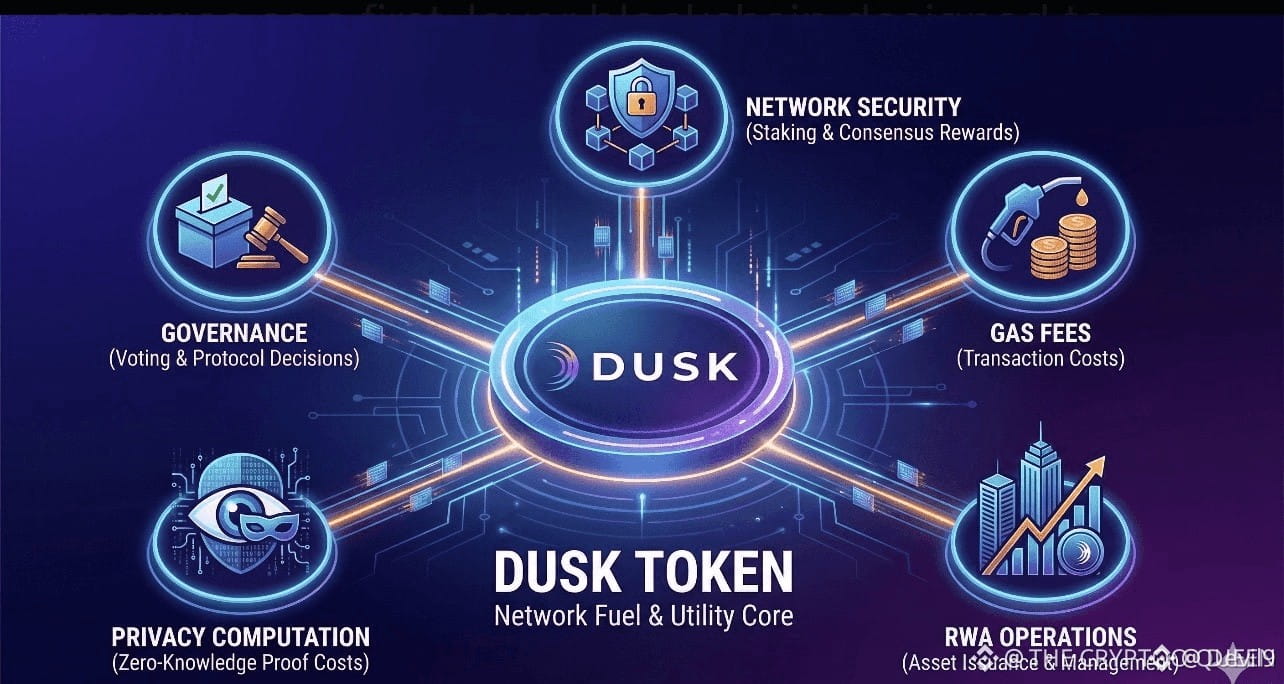

The Dusk Foundation design approach starts from the assumption that privacy in regulated markets is controlled disclosure, not full anonymity. Instead of “hide everything forever,” the goal is: keep transaction details confidential by default, but make it possible to reveal specific facts selectively, cryptographically, and with consent when a regulator, auditor, or counterparty is authorized to see them. This changes the architecture: privacy is not a separate optional lane that only some users take; it’s part of the normal transaction lifecycle, so the assurance story is more uniform. In contrast, on Ethereum the base layer’s transparency creates friction for sensitive activity, so privacy often arrives through L2s, app-specific zk systems, or specialized contracts. Those approaches can be valid, but they add dependencies (bridges, provers, sequencers/relayers, and new composability constraints) that institutions must evaluate as part of their risk model.

On consent and fast finality (high level), the institutional requirement is not “fast for trading hype,” but “fast enough to reduce settlement risk while keeping governance and disclosure rules enforceable.” A system that can finalize transactions predictably helps with operational controls: reconciliation windows shrink, margin and collateral rules can be enforced more deterministically, and disputes are easier to bound. The key is that finality and privacy can’t fight each other; you want confidential execution that still yields clear, verifiable settlement.

Dusk’s dual transaction models Moonlight and Phoenix can be understood as two rails optimized for different disclosure and data-handling needs. One model supports richer programmability and account-style interactions; the other is optimized for privacy-preserving transfers and simpler flows. From an institutional viewpoint, the important part isn’t the branding; it’s that the protocol acknowledges different transaction shapes and compliance expectations, and tries to support them without forcing everything through a single “one size fits all” privacy wrapper.

Audit and controlled disclosure is where “built-in privacy” shows its practical value. A regulated workflow needs an audit trail that is both privacy-preserving and legally usable: you need to prove that rules were followed (eligibility, limits, disclosures, settlement integrity) without exposing all counterparties and amounts to the public. If privacy is embedded at the protocol level, the disclosure mechanism can be standardized: clients can generate proofs and selectively reveal fields to authorized parties, while third parties can verify correctness without learning the underlying private data. With add-on privacy stacks, you often end up with multiple disclosure formats across L2s and apps—fine for experimentation, harder for institutional assurance at scale.

For regulated markets, smart contracts are not just “code that runs,” they’re instruments with lifecycle obligations: issuance terms, transfer restrictions, corporate actions, reporting hooks, and settlement rules. Jaeger (as described in the Dusk ecosystem) is positioned around expressing those instruments in a way that aligns with compliance: embedding constraints, supporting privacy-preserving interaction, and enabling verifiable state transitions that an auditor can validate when permissioned. The institutional payoff is straightforward: you can model instruments so that compliance checks are not external paperwork bolted onto an otherwise permissionless flow, but part of the transaction logic while still keeping sensitive details off the public surface area.

Even with protocol-level privacy, real-world deployment depends on governance choices, implementation quality, and the willingness of institutions and regulators to standardize on specific disclosure practices. “Controlled disclosure” also introduces operational questions: who holds view keys, how access is granted and revoked, how disputes are handled, and how to prevent permissioned visibility from turning into brittle central points of failure. And while built-in privacy can reduce L2 dependency risk, it doesn’t eliminate all external constraints legal enforceability, custody integration, and cross-venue settlement remain hard problems that no single protocol design can fully solve.

Raksts

Dusk Foundation Integrated Protocol Privacy vs.Add-on Privacy:Dusk vs Ethereum’s L2 Privacy Stack”

Atruna: iekļauti trešo pušu pausti viedokļi. Šī informācija nav uzskatāma par finansiālu padomu. Var būt iekļauts apmaksāts saturs. Skati lietošanas noteikumus.

DUSK

0.1028

-10.37%

ETH

2,234.65

-7.31%

0

6

250

Uzzini jaunākās kriptovalūtu ziņas

⚡️ Iesaisties jaunākajās diskusijās par kriptovalūtām

💬 Mijiedarbojies ar saviem iemīļotākajiem satura veidotājiem

👍 Apskati tevi interesējošo saturu

E-pasta adrese / tālruņa numurs