原文标题:Towards understanding governance tokens in liquiditymining: a case study of decentralized exchanges

Original source: cuhk

Original author: Sizheng Fa, Tian Min, Xiao Wu, Cai Wei

Compiled by: LXDAO

Introduction

Recently, Erin Koen, head of governance at Uniswap, initiated a proposal in the forum to improve the protocol's governance system and fee mechanism. He proposed that users who staked and delegated UNI governance tokens should be allocated a proportional share of protocol fees to incentivize and strengthen Uniswap's governance. This proposal was welcomed by the UNI community, and the price of the UNI token rose by 60% in one day.

I noticed another concern about this proposal within the LXDAO community, including within the broader web3 community: this is also an adjustment to fee distribution and incentives, and UNI token holders will benefit from this change.

For this LXDAO translation, we chose the research article "Towards understanding governance tokens in liquidity mining: a case study of decentralized exchanges" published in July 2022, written by Sizheng Fan, Tian Min, Xiao Wu, and Cai Wei from the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Due to limited time and ability, the author omitted part of the "method" content, most of the data graphs and references in the original text, and edited the title for readability, but tried to translate it accurately and added reminders in relevant places.

In the study, the authors used data analysis to reproduce the "vampire attack" of the DeFi summer in 2020. It was in response to the attack from SuShiSwap that the UNI governance token was born. We can see that governance tokens have two purposes since their inception - governance and incentives, which are entangled between the ideals of web3, commercial competition, and incentive mechanisms. I believe this article will help everyone understand the background and motivation of Uniswap's proposal, and prompt everyone to think about broader issues and possibilities about web3.

text

The article is about 11,000 words and is divided into 8 parts.

1. Abstract

2. What is liquidity mining?

3. Blockchain as a method

4. Discovery

5. Background

5.1 Ethereum and Modern Cryptocurrency

5.2 Impermanent Loss

5.3 Development History of Uniswap and SushiSwap

6. Recreate a vampire attack

6.1 Dataset

6.2 Contracts and Functions

6.3 Data Collection

6.4 Dataset Analysis Results

6.5 Total Liquidity Value (TVL)

6.6 Called function type

6.7 Time distribution of new users and new liquidity providers

6.8 Clustering Results Analysis

6.9 Liquidity Provider Behavior in Uniswap

6.10 Overlapping Addresses

7. Conclusion

8. The Future

1. Article Abstract

Liquidity mining is a hot topic in the decentralized finance (DeFi) community, which has greatly increased the total locked value (TVL). In order to attract users, most decentralized applications (DApps) distribute governance tokens in liquidity mining.

However, there is still a lack of in-depth evidence on the effectiveness of this method. This article takes a typical case as an example to explore the governance tokens in liquidity mining: SushiSwap attracted a large amount of Uniswap liquidity in a short period of time by copying Uniswap’s code and issuing governance tokens in advance.

We collected more than a year of transaction data from Uniswap and SushiSwap and conducted a detailed analysis of the behavior of liquidity providers (LPs). We also designed a scalable unsupervised clustering method to construct a similarity graph using metrics from transaction flows and discovered patterns of liquidity providers with similar behaviors. These patterns range from inactive and cautious liquidity providers, to liquidity providers that provide tiny liquidity, to liquidity providers that seek risk in the short term, etc.

Based on this, we discuss the impact of governance tokens on liquidity mining and use their impact on behavior and decision-making to explain their appeal to users.

2. What is liquidity mining?

Liquidity mining is a mechanism that incentivizes users to provide liquidity to decentralized exchanges (DEXs). It was first proposed by IDEX in 2017 and further improved by Synthetix and Chainlink in 2019. In mid-2020, liquidity mining ushered in explosive development, with projects such as Compound, SushiSwap, and Uniswap joining in. Liquidity mining has become an important part of the DeFi community. According to DeFi Pulse, the total locked value (TVL) in the market was $1.05 billion in early June 2020. By September, the community's promotion had increased TVL by 10 times. This amazing growth and enthusiasm is comparable to the boom of initial coin offerings (ICOs) in 2017.

Liquidity mining is a mechanism that incentivizes users to provide liquidity to a DEX, similar to bank deposits. Users can deposit token pairs in a DEX based on an automated market maker (AMM) and use smart contracts to trade without an order book. Traders can exchange one token for another in a DEX. After each transaction, the DEX charges a certain transaction fee, which is rewarded to liquidity providers as interest. In addition, liquidity providers can also receive governance tokens as a stake in the protocol to encourage their participation. Governance tokens are a type of cryptocurrency that has voting rights that represent blockchain projects. In recent years, governance tokens have been widely used in DeFi projects to achieve decentralized decision-making for users. Governance tokens also have economic value and can be traded in centralized exchanges (CEXs) and DEXs. The number of governance tokens issued is specified by the protocol and usually shows a decreasing trend.

Currently, most decentralized protocols have adopted liquidity mining as an innovative and efficient way of decentralization. By adding governance token rewards to liquidity mining, protocols can attract more liquidity providers, such as SushiSwap's "vampire attack" on Uniswap. However, the effectiveness of this method lacks in-depth analysis.

3. Blockchain as a method

To answer how governance tokens affect user strategies, a direct approach is to conduct user surveys. However, in the blockchain field, this approach is costly and difficult to implement. To obtain representative survey results, a large amount of user information needs to be collected. It is not easy to send questionnaires by wallet address or to screen users who participate in governance tokens from the blockchain community. Moreover, using cryptocurrency as a reward also brings a huge economic burden. Therefore, we chose a smarter way to get the information we need from open source data.

This article uses a specific case as an example to explore the impact of governance tokens on liquidity mining: SushiSwap launched a "vampire attack" on Uniswap by issuing the governance token SUSHI and permanently incorporating it into the rewards for liquidity mining, thereby attracting a large amount of liquidity. After that, Uniswap also issued the governance token UNI and used it as a reward for liquidity mining in the two months from September 18 to November 18, 2020. Based on the differences in the issuance time and reward cycle of governance tokens in this case between Uniswap and SushiSwap, we analyzed the impact of governance tokens on liquidity mining from the following two aspects.

1. Macro level: We analyzed the macro data of Uniswap and SushiSwap, and explored the impact of external factors such as ETH price and incentive policies on the total locked value (TVL), function calls, and the number of users.

2. Micro level: We performed unsupervised clustering of liquidity providers and compared the behavioral changes before and after the vampire attack to reveal the sensitivity of different types of liquidity providers to incentives.

4. Discovery

Our main contributions are as follows:

Database Construction: We briefly introduced the major events of two decentralized exchanges, Uniswap and SushiSwap. Uniswap is the most popular decentralized exchange on Ethereum, while SushiSwap is the earliest and most prominent Uniswap fork project. Although the transparency of blockchain guarantees the open source of on-chain data, it is still a difficult task to integrate, preprocess and extract usable data. We collected nearly a year of fine-grained transaction data, covering records of about 300,000 addresses of these two exchanges, to build the database.

Transaction flow extraction and clustering: We first proposed a method to format address transaction flow and implemented it based on our database. We also used an unsupervised hierarchical clustering method to classify liquidity providers into six categories based on their behavioral characteristics: dispensable, lightly active, lightly inactive, medium risk-averse, medium risk-seeking, and heavy risk-seeking.

Results analysis: The clustering results show that governance token rewards can attract more liquidity providers in the short term, but then these liquidity providers tend to withdraw liquidity in pursuit of higher income, resulting in a decline in annualized percentage yield (APY) and losses, especially for medium and heavy liquidity providers. Such behavior is not in line with the original intention of governance tokens, and will trigger a vicious cycle, making traders more susceptible to slippage, further reducing the returns of liquidity providers. In addition, by comparing the proportion of overlapping liquidity providers in SushiSwap and Uniswap within one year, we found that: under the long-term incentive of SUSHI governance tokens, SushiSwap has gradually cultivated a group of exclusive stable liquidity providers.

5. Background

5.1 Ethereum and Modern Cryptocurrencies

Ethereum is a blockchain platform based on Bitcoin's innovation. It provides developers with an end-to-end system for building mainstream software applications. It has pioneered a new computing paradigm: a trustful object messaging compute framework. Smart contracts are distributed scripts that do not require external trust agencies and are executed synchronously on multiple nodes of the blockchain.

Ethereum-based cryptocurrencies all follow the ERC-20 standard and have several common features, one of which is tradability. They all have a fixed and limited supply of tokens and use the Ethereum blockchain, which is publicly viewable by anyone. In addition, the owner of the token can freely transfer control of the token. These features facilitate the formation of a market where users can trade tokens, whether through exchanges (both decentralized and centralized) or in a peer-to-peer manner.

5.2 Impermanent Loss

As mentioned above, liquidity mining is simply a passive income method that helps cryptocurrency holders to profit by leveraging existing assets instead of letting them sit idle in their wallets. Assets are deposited into decentralized exchanges, and in return, the platform distributes the fees earned by the exchange proportionally to each liquidity provider. Temporary losses, also known as deviation losses, refer to the losses that funds are exposed to in the liquidity pool. This loss usually occurs when the ratio of tokens in the liquidity pool changes, which means that users suffer negative returns compared to just holding their tokens without putting them into the liquidity pool. In this case, DeFi protocols tend to compensate liquidity providers using the transaction fees paid by traders. Some even add additional rewards - governance tokens to attract more liquidity.

5.3 Development History of Uniswap and SushiSwap

The development of Uniswap and SushiSwap can be divided into four stages: the steady growth period, the vampire attack, the counterattack of Uniswap, and the boom period.

The first version of Uniswap, Uniswap V1, was launched on the Ethereum mainnet on November 2, 2018. The initial liquidity of this version was only $30,000, consisting of three tokens. However, Uniswap V1 was designed to only support automatic conversions between ETH and ERC-20 tokens, which means that each liquidity pool must contain ETH. Therefore, transactions between ERC-20 tokens need to be mediated by ETH, which increases gas fees, commissions, and slippage. In other words, the exchange between tokens requires two transactions instead of one.

Steady growth period (May 19, 2020 - August 28, 2020): In May 2020, Uniswap released its second version, whose main feature is to support direct exchange between ERC-20 tokens, which greatly reduces transaction costs and time, and also reduces the risk of temporary losses faced by liquidity providers. In addition, Uniswap V2 also added some new features, such as on-chain price oracles and lightning transactions.

Vampire Attack (August 28, 2020 - September 17, 2020): At the end of August, SushiSwap joined the market. It is a clone of Uniswap, but it provides governance token rewards to Uniswap liquidity providers, with the goal of moving Uniswap's liquidity to its own platform and competing directly with Uniswap. Specifically, the first step of the vampire attack was to reward Uniswap liquidity providers with SUSHI tokens, who were required to stake UNI-V2 tokens on SushiSwap. SushiSwap has an incentive plan for SUSHI tokens: 1,000 SUSHI will be distributed to Uniswap liquidity providers every Ethereum block, covering multiple liquidity pools. Once enough liquidity is transferred, the staked UNI-V2 tokens will be migrated from Uniswap to SushiSwap. Ultimately, SushiSwap not only took away liquidity, but also took away Uniswap's trading volume and users.

Uniswap Strikes Back (September 18, 2020 - November 18, 2020): To combat SushiSwap’s vampire attack, Uniswap launched its own token, UNI, on September 16. Surprisingly, a portion of UNI was distributed retroactively. Any address that had interacted with Uniswap before September 1 was eligible to claim 400 UNI, worth about $1,200 at the time. In addition, Uniswap created four liquidity pools and incentivized liquidity providers with additional UNI tokens over the next two months, which resulted in millions of dollars in additional liquidity.

Boom period (November 18, 2020 - May 19, 2021): After stopping issuing additional governance tokens, Uniswap's total locked value (TVL) briefly declined. However, starting in November 2020, as the prices of Ethereum and Bitcoin rose, Uniswap and SushiSwap's trading volume and total locked value grew rapidly as more funds poured into the entire DeFi ecosystem.

6. Recreate a vampire attack

6.1 Dataset

To study the incentive effect of governance tokens in liquidity mining, we used SushiSwap’s vampire attack on Uniswap and Uniswap’s counterattack as examples, and obtained public records from Etherscan of addresses that interacted with the contracts of the two platforms from May 2020 to July 2021. Based on this data, we found the following:

Although Uniswap’s trading volume is ten times that of SushiSwap, SushiSwap’s liquidity provider address ratio is twice that of Uniswap. This may indicate that SushiSwap’s perpetual governance token distribution can increase the participation of liquidity providers.

Although both Uniswap and SushiSwap provide the same services, the proportion of users using these services is different. On Uniswap, users tend to trade tokens through ETH, while on SushiSwap, users trade tokens directly with each other more often.

6.2 Contracts and Functions

DEX router contracts are integrated interfaces that can be used to exchange different token pairs or manage liquidity. Therefore, we can track the behavior of all DEX users through router contracts.

To achieve these functions, the router contract contains a variety of functions related to token trading and liquidity. These functions are generally used as interfaces to complete specific operations by calling core contracts. In our dataset, the Uniswap core contract called 26 functions and the SushiSwap core contract called 33 functions. 21 of them are the same.

According to their functions, these functions can be roughly divided into three categories:

“Swap” functions, used to implement ETH/token or token/token transactions in different situations; “add/remove” functions, used to increase or decrease liquidity in ETH or token pairs; and “utility” functions, used for query, management or emergency response.

In order to adapt to all possible transaction scenarios, these functions generate different variants according to certain naming rules, as shown in the figure below. Therefore, we can filter out addresses that use specific functions by filtering keywords.

Figure 1: Function naming convention

Figure 1: Function naming convention

6.3 Data Collection

We obtained the external transaction records before July 2021 in block order. Then, we grouped the external transactions according to the wallet address and obtained the list of users interacting with the DEX. Next, we used the application binary interface (ABI) of the router contract to decode the input value of each transaction and obtained the corresponding function object (func_obj) and parameters (func_param). On this basis, we filtered out liquidity providers by keywords in the function name. We also built a series of dictionaries to classify function objects to generate attributes (func_type). Finally, we extracted liquidity data by the keywords "add liquidity" or "remove liquidity" in the function type.

While processing external transactions, we also obtained their ERC-20 transaction records based on the list of addresses participating in liquidity activities. From the ERC-20 token transaction log, we can find the number of token pairs that liquidity providers gain or give up when adjusting liquidity based on the transaction hash, and then convert it into US dollars based on the price on the day of the transaction. After the above preprocessing steps, we can get the timestamp and amount of liquidity changes for each liquidity provider, which can be formatted as a time series for further analysis.

As of July 2021, the transaction records of Uniswap and SushiSwap router contracts were 46,077,169 and 2,030,355 respectively. Grouped by address, 2,310,175 and 160,345 different addresses were obtained, of which 297,345 and 43,705 addresses participated in liquidity provision, accounting for 12.8% and 27.2% of the total number of addresses. Comparing the address lists of the two platforms, it was found that there were 50,176 duplicate addresses, of which 27,521 were duplicate liquidity providers.

We divide the functions of the router contract into five categories according to the naming conventions of the functions called by the Uniswap and SushiSwap contracts and their functions. Among them, three categories are "Swap" functions: "ETH-Token", "Token-ETH" and "Token-Token", which correspond to the three trading pairs on DEX respectively; the other two categories are liquidity functions: "Add Liquidity" and "Remove Liquidity".

In the table, # Called indicates the number of times the corresponding function is called, % Called indicates the percentage of the corresponding function in the total number of calls, and % Called by Address indicates the percentage of addresses that have called the corresponding function in the total number of addresses.

Table 1: Number of calls to corresponding functions in Uniswap

And the percentage of addresses that have called the corresponding function to the total addresses

Table 2: Number of calls to corresponding functions in SushiSwao

And the percentage of addresses that have called the corresponding function to the total addresses

From the statistics, we can see that although Uniswap and SushiSwap provide the same services, their users have different usage habits. Uniswap has far more users than SushiSwap, but in terms of % Called by Address, the usage of the five types of functions by users of the two platforms is not proportional. Uniswap users use the "Swap" function more, especially ETH-token transactions. On SushiSwap, users are more inclined to conduct token-token transactions, which account for 34.69% of the number of users and contribute 31.59% of the transaction volume. In addition, SushiSwap's liquidity function is higher than Uniswap in terms of the number of calls and user percentage.

Methodologically, we format transaction flows, build similarity graphs of transaction flows, and use unsupervised clustering algorithms to capture user groups with similar behaviors (Editor's note: there is a section in the original text that describes the methodology in detail, which is omitted in the translation here).

6.4 Dataset Analysis Results

We explore the impact of governance tokens on liquidity mining based on time series data and the behavior of liquidity providers.

Adding governance token rewards to liquidity mining can significantly increase the total liquidity value and the number of liquidity providers in the short term. However, this is not a particularly effective measure in the long run.

Liquidity providers that provide less liquidity have less activity in DEX, but the most active liquidity providers do not necessarily come from the addresses that provide the most liquidity in DEX. Some medium-sized liquidity providers add and remove liquidity more frequently to participate in liquidity mining of multiple protocols and earn governance tokens. In contrast, heavy liquidity providers tend to pursue long-term transaction fee income and are less affected by other external factors.

6.5 Total Liquidity Value (TVL)

Next, let’s analyze the changing trends of the total liquidity value (in USD) of Uniswap and SushiSwap from August 2020 to 2021 in chronological order.

Figure 2: Total liquidity and daily trading volume of Uniswap and SushiSwap

Figure 2: Total liquidity and daily trading volume of Uniswap and SushiSwap

First, there was the vampire attack. At this stage, the attack on SushiSwap caused Uniswap's liquidity to drop significantly, from about $3 billion to nearly $2 billion, and further to about $500 million within a few days, although this value is still higher than a week ago. However, Uniswap's trading volume remains high at about $300-800 million per day. Therefore, we can infer that although SushiSwap incentivizes liquidity mining by issuing governance tokens, some liquidity providers still have confidence in Uniswap's trading volume and therefore choose to stay in Uniswap to obtain commission income.

On September 18, 2020, Uniswap launched a counterattack, and its total liquidity value quickly surpassed SushiSwap, and maintained an overwhelming advantage until November 18, 2020, when Uniswap's liquidity mining activity incentivized by UNI governance tokens ended, at which time a large number of Uniswap liquidity providers switched to SushiSwap. On September 18, when the UNI token was released, this event brought $1.65 billion in total liquidity value to Uniswap, while SushiSwap lost $159 million in total liquidity value on the same day. In the following two months, Uniswap's total liquidity value continued to rise until it peaked at $3.06 billion on November 14. After that, with only three days left before the end of the event, some liquidity providers began to withdraw liquidity, causing the total liquidity value to drop slightly. On November 18, Uniswap’s total liquidity value plummeted by US$1.29 billion, while SushiSwap’s total liquidity value rose by US$578 million, once again causing a phenomenon similar to a “vampire attack”.

After November 18, 2020, the total liquidity value of Uniswap and SushiSwap began to move in line with the price trend of ETH. In particular, on January 6, 2021 and April 1, 2021, the growth of total liquidity value was accompanied by a sharp increase in the price of Ethereum. This can be explained by the fact that the price and exchange rate of ETH as a major currency directly affect the total liquidity value in US dollars. From a market perspective, the increase in the price of Ethereum may have activated the blockchain market, resulting in more frequent token transactions. Therefore, liquidity providers can increase their income by participating in more transactions.

The fluctuations in trading volume are not clearly correlated with the selected events, but rather with the ETH price. However, changes in trading volume also mean changes in commission income for liquidity providers. Therefore, the governance token plays an important role in incentivizing the total liquidity value of SushiSwap, even though its trading volume is always lower than Uniswap.

After November 18, 2020, the total liquidity values of Uniswap and SushiSwap began to coincide with the price fluctuation trend of ETH. In particular, on January 6, 2021 and April 1, 2021, the increase in total liquidity value was accompanied by a sharp rise in the price of Ethereum. This can be explained by the fact that the price and exchange rate of ETH as a major currency directly affect the total liquidity value calculated in US dollars. From a market perspective, the appreciation of Ethereum may lead to a more active blockchain market, which means more frequent token transactions. Therefore, liquidity providers can earn more by participating in more transactions.

The volume chart tells us that fluctuations in volume are not particularly precisely correlated with selected events, but rather with ETH prices. However, changes in volume mean changes in commission earnings for liquidity providers. Therefore, governance tokens play a key role in incentivizing the total liquidity value of SushiSwap, even though its volume is always lower than Uniswap.

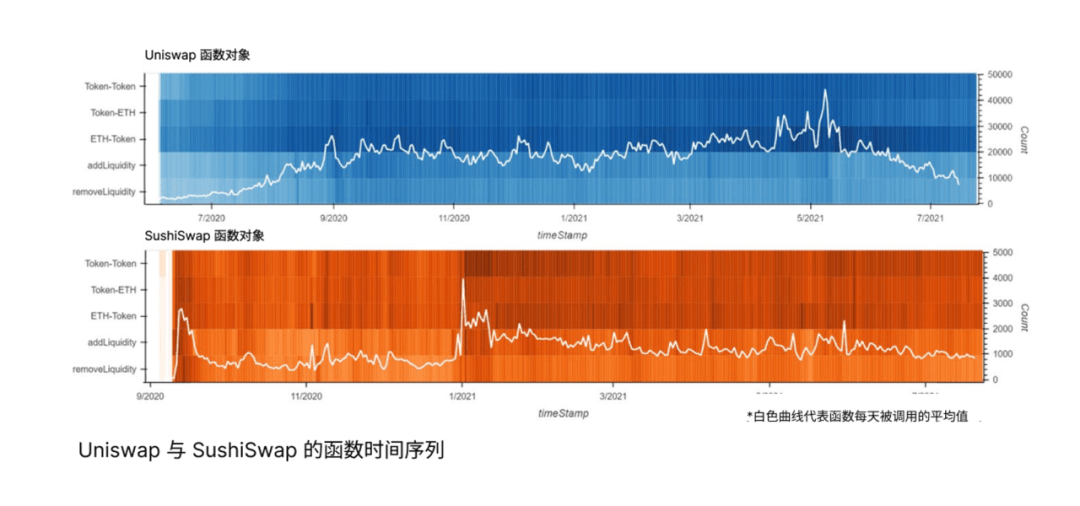

6.6 Types of functions called

We obtained time series data for five functions (‘ETH-Token’, ‘Token-ETH’, ‘TokenToken’, ‘Add Liquidity’ and ‘Remove Liquidity’) based on the number of function calls per day.

Figure 3: Functional time series of Uniswap and SushiSwap

Figure 3: Functional time series of Uniswap and SushiSwap

The above chart shows the activity of liquidity providers within 3-4 days after the issuance of the governance token. It can be seen that the announcement of SUSHI rewards increased the frequency of function calls on Sushiswap, especially the "add liquidity" function. But after the vampire attack, although the "add liquidity" function continued to run at a high level for a few days, it was accompanied by an increase in the "remove liquidity" function. There may be two reasons for this: one is that SUSHI rewards have decreased over time, prompting some liquidity providers to withdraw funds; the other is that Uniswap has taken countermeasures. This is consistent with the competitive strategy of the two platforms in early September.

In addition, the five functions will increase sharply at the same time in certain periods, such as the Uniswap heat map in September 2020 and the SushiSwap heat map in January 2021. We can see that all five lines present a vertical dark pattern. Looking at each row, the Swap class function is called less than the liquidity class function. For Uniswap, the function of exchanging tokens for ETH is more significant than other functions, which to a certain extent reflects the main purpose of users interacting with Uniswap.

6.7 Time distribution of new users and new liquidity providers

Figure 4: New users and liquidity providers for Uniswap and SushiSwap respectively

Figure 4: New users and liquidity providers for Uniswap and SushiSwap respectively

We obtained the timestamps of the first interaction with the DEX and the first liquidity provided by the address from the transaction records of the two DEXs and drew the above figure. Although some addresses first acted as traders and later became liquidity providers, this does not affect our statistics of the number of new users or new liquidity providers by date and their time characteristics. It is worth noting that the transaction volumes of Uniswap and SushiSwap are very different, resulting in the difference in the vertical axis in the figure, but this does not prevent us from finding useful information from the trend.

By comparing the two curves of new users and new liquidity providers in the figure, we can infer the motivations of users to use Uniswap or SushiSwap in different periods.

Judging from the Uniswap curve, the changes in the two curves are inconsistent, which is consistent with Uniswap’s high trading volume: most users use Uniswap for trading. In early September 2020, during the vampire attack, the curve of new liquidity providers showed two prominent peaks.

On the contrary, SushiSwap’s curve shows that the two curves only converged in January 2021, which shows that most of SushiSwap’s users are providing liquidity and obtaining SUSHI rewards, rather than trading.

In addition, we can also find the volatility patterns in September and November 2020 and January and May 2021. This shows that some special events, such as the rise in Ethereum prices or policy changes, have a certain impact on user behavior and motivation, and can attract more new users to join. For example, after January 2021, as the price of ETH rose, the number of daily new users of Uniswap and SushiSwap also increased accordingly, reaching a peak in May 2021, and then gradually declined and stabilized. This macro volatility related to the blockchain market is not closely related to the services and user interests of DEX itself.

6.8 Clustering Results Analysis

We grouped liquidity providers into six categories based on the on-chain activity of their addresses to analyze their purpose of interacting with DEXs. We clustered Uniswap and SushiSwap separately.

Dispensable liquidity providers are those addresses that provide a small amount of liquidity and lack the enthusiasm to participate. In Uniswap and SushiSwap, they account for 58.1% and 17.2% respectively. Their total locked value is low (less than $1,000) and the operation interval is large. We speculate that these addresses just want to try liquidity mining and are unwilling to invest too much money.

Light liquidity providers are those addresses that provide more liquidity. In Uniswap and SushiSwap, they account for 18.0% and 42.2%, respectively. Light liquidity providers can be divided into two sub-clusters based on the frequency of operation, namely inactive light liquidity providers and active light liquidity providers. Active light liquidity providers interact more frequently with DEXs, especially in Uniswap. Although the proportions of light liquidity providers and dispensable liquidity providers are different in the two DEXs, the sum of their proportions exceeds 59%, which shows that in both DEXs, liquidity providers that provide a small amount of liquidity account for the vast majority. In addition, the higher proportion of light liquidity providers in SushiSwap suggests that long-term governance token rewards can attract more small users to participate in liquidity mining.

Medium liquidity providers refer to those addresses that provide higher liquidity. In Uniswap and SushiSwap, they account for 19.9% and 29.7%, respectively. Medium liquidity providers are further subdivided into risk-seeking medium liquidity providers and risk-averse medium liquidity providers. The two types of medium liquidity providers have similar liquidity distribution values, but different numbers of operations. Specifically, risk-averse medium liquidity providers are more cautious or negative due to concerns about potential losses. However, risk-seeking medium liquidity providers like to provide liquidity in multiple DEXs to obtain governance token rewards with high annualized returns, even if they may face the risk of temporary losses or theft of funds.

Heavy liquidity providers are those addresses that provide a large amount of liquidity. In the two DEXs, they have the lowest proportion, accounting for 4.6% and 11% respectively. Their liquidity scale in DEX is large. For example, the address 0xf0fc provides more than 14 million USDC and 7861 ETH in Uniswap, which is worth nearly 30 million US dollars at the time. In addition, compared with the risk-seeking medium-sized liquidity providers, these addresses have lower operation frequency, which shows that they are more inclined to pursue long-term commission income and their decisions are less affected by other external factors.

6.9 Liquidity Provider Behavior in Uniswap

In this section, we have collected a list of Uniswap liquidity provider addresses that operated liquidity or called special contracts during a specific period. The period started on August 28th and ended on November 18th when Uniswap stopped UNI token incentives.

Since SushiSwap launched the Masterchef contract, which allows users to stake UNI-V2 tokens to earn SUSHI, many new addresses have flocked to Uniswap to provide liquidity in order to obtain UNI-V2 tokens. In just ten days, the incremental liquidity providers on Uniswap were nearly ten times the sum of the previous three months. Among these new liquidity providers, the proportion of heavy liquidity providers and medium liquidity providers is much higher than that of returning liquidity providers. We found that between August 28 and September 8, more than half of the liquidity providers staked their UNI-V2 tokens to MasterChef to obtain more SUSHI, while less than 5% of the returning liquidity providers did so. We speculate that this is because dispensable liquidity providers account for a high proportion of returning liquidity providers, who are less active and do not provide much liquidity. Therefore, they may not be sensitive to market information and do not care about SUSHI because they have less capital investment and cannot obtain a large amount of SUSHI.

In the next stage, we noticed that nearly half of the addresses that earned SUSHI withdrew liquidity within the next two months. According to the withdrawal time, we divided it into two periods: September 9 to September 17 (Period A); and September 18 to November 18 (Period B). First, 26.7% of liquidity providers chose to withdraw liquidity in Period A. Among them, 57.7% were medium-sized liquidity providers and heavy-duty liquidity providers. We believe that this part of liquidity providers is most sensitive to the market and pays the most attention to liquidity income. They only provide liquidity in periods with higher yields. Second, 21.2% of addresses chose to withdraw liquidity from SushiSwap in Period B. We speculate that this is because Uniswap released UNI and started liquidity mining on September 18, and the transaction fee income and higher annualized yield brought by Uniswap's high daily trading volume quickly attracted back some of the liquidity providers who flowed out of SushiSwap. Finally, after UNI stopped issuing on November 18, only a very small number of addresses in this group migrated liquidity to SushiSwap by calling the Migrator contract.

6.10 Overlapping Addresses

Uniswap and SushiSwap have 297,345 and 43,705 independent addresses that have provided liquidity, respectively, of which 27,521 addresses provide liquidity for both exchanges at the same time. This section will analyze the clustering characteristics of these overlapping addresses.

Figure 5: September 8, 2020 to November 18, 2020

Figure 5: September 8, 2020 to November 18, 2020

and September 8, 2020 to July 18, 2021

Short-term and long-term changes in overlapping addresses in the SushiSwap cluster

The data shows the short-term and long-term changes in overlapping addresses in the SushiSwap cluster. In early September 2020, SushiSwap launched a vampire attack, but this advantage quickly disappeared after Uniswap launched liquidity mining and UNI. As of November 2020, we can see that there is a large overlap between Uniswap and SushiSwap liquidity providers in the first two months of SushiSwap. Specifically, 87.2% of SushiSwap heavy liquidity providers have overlapping addresses, of which 76% are classified as medium liquidity providers and heavy liquidity providers on Uniswap. However, nearly a year after SushiSwap was launched, data from July 18, 2021 showed that the proportion of overlapping addresses has decreased, among which the overlap rate of SushiSwap heavy liquidity providers has decreased by 41.4%. Therefore, we can conclude that SushiSwap has gradually cultivated an exclusive group of stable liquidity providers over the past year through long-term SUSHI incentives.

7. Conclusion

We demonstrate that adding a governance token to liquidity mining has different appeals to different types of liquidity providers.

Based on the clustering results, taking SushiSwap as an example, we found that more than 50% of heavy liquidity providers and medium liquidity providers would withdraw funds in a short period of time. We summarized two reasons behind this phenomenon:

1) High rewards from competitors (Uniswap);

2) The annualized rate of return on rewards decreases over time.

Therefore, rewards in the form of adding governance tokens do not work well in the early stages of the protocol.

We found that the most active participants in liquidity mining are not those with the most funds, but rather those with moderate funds. The reason for this phenomenon is that this group of addresses has the strongest subjective motivation to pursue benefits and rewards, so we infer that incentives such as governance tokens should be the most attractive to them.

From a more macro perspective, all these concerns about the impact of governance tokens show that it has not played the governance value designed, but has been used as an arbitrage tool by relatively well-funded speculators, without having a positive impact on the development of the protocol. However, at the same time, we note that the neglect of governance capabilities has not weakened its attractiveness to users. By comparing the overlapping liquidity provider ratios of SushiSwap and Uniswap in the two stages, we found that SushiSwap has gradually gained a stable user base and scale through long-term governance token issuance and business innovation.

8. The Future

Protocols often attract users by adding governance tokens to liquidity mining. Our analysis shows that although this method can attract more users in the short term, it is difficult to retain them. Therefore, protocols should seek other ways to attract users, such as reducing transaction costs and providing more convenient functions.

In addition, governance tokens are the basis of community autonomy and an important part of any Web 3.0 protocol. Liquidity mining, as a pioneer in distributing governance tokens, can only encourage liquidity providers to participate passively rather than actively contribute. We realize that higher barriers to participation, such as rising gas fees and sufficient liquidity, will hinder liquidity providers with insufficient funds. Therefore, exploring new ways to distribute governance tokens is crucial for the Web 3.0 community. Decentralized communities need to explore new incentive mechanisms that can actively motivate members to participate in governance. For example, participants can make suggestions related to protocol development, and if the community adopts these suggestions, the proposers will be rewarded with governance tokens. Future research can explore, model, and evaluate optimized governance mechanisms to build better decentralized communities.