The first time Walrus really clicked for me, it was not because of a benchmark or a bold claim. It was because it felt oddly practical. In Web3, storage is usually treated like a warehouse. You put files somewhere, copy them a few dozen times, and hope they are still there when someone needs them. Walrus challenges that assumption. It does not treat data as something you dump and forget. It treats data as something alive. Something that needs to stay available, verifiable, and fast, even when parts of the system fail or change. That shift sounds subtle, but it has real consequences for how applications are built.

At the heart of Walrus is a different way of thinking about resilience. Most decentralized storage systems rely heavily on replication. The idea is simple: copy the same file many times so that if some copies disappear, others remain. The problem is cost and inefficiency. Walrus uses a design called Red Stuff, which relies on erasure coding instead of brute-force copying. In simple terms, a file is broken into many pieces and encoded with redundancy in two dimensions. If some pieces go missing, the system can reconstruct them using the remaining ones. It is similar to how modern error correction works in data transmission. You do not resend everything, only what is needed. The result is storage that can heal itself under churn without excessive bandwidth or storage waste. This is not about being clever for its own sake. It is about making large data usable at scale without pushing costs out of reach.

What really separates Walrus from many storage projects is how tightly it connects data to applications. Storage is not hidden behind the scenes. Through its integration with Sui’s object model, storage capacity and data blobs can be represented as resources that applications can reference. This matters because it allows apps to reason about data availability instead of blindly trusting it. In some designs, smart contracts can even verify whether data is still accessible through onchain coordination. That turns storage into part of the application logic rather than a silent dependency. For developers, this changes the mindset. Data is no longer just “somewhere off-chain.” It becomes something the app can check, track, and respond to when conditions change.

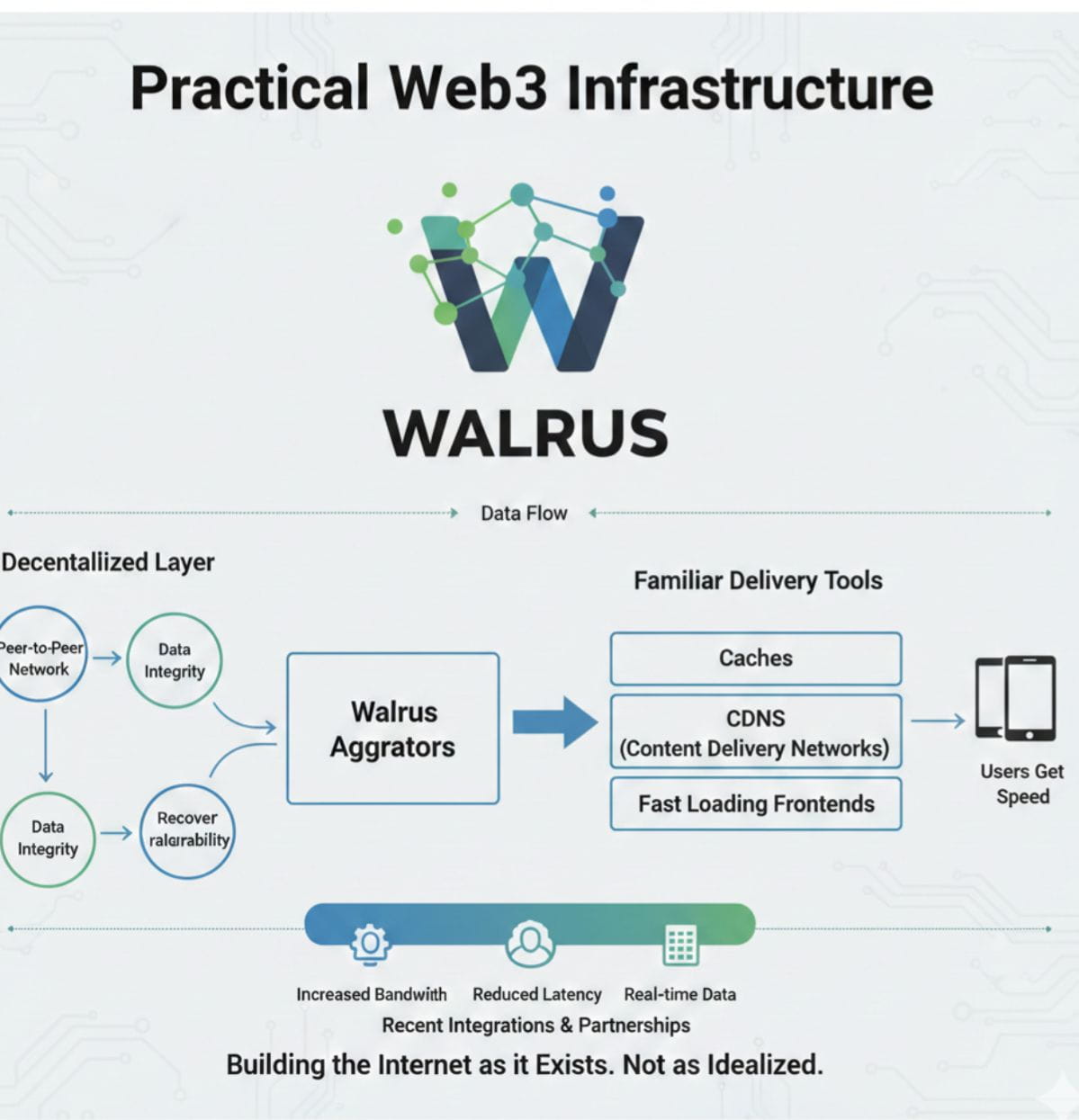

Speed is another area where Walrus makes a grounded choice. Many Web3 systems pretend that traditional infrastructure does not exist, or worse, that it should be replaced entirely. Walrus does not play that game. It accepts a simple truth: users expect fast loading times. Frontends cannot wait for slow peer-to-peer retrieval when a page loads. Walrus is designed so that data access can flow through aggregators and be served via caches or CDNs. This does not undermine decentralization. It complements it. The decentralized layer ensures data integrity and recoverability, while familiar delivery tools handle performance. Users get speed. Developers avoid painful trade-offs. The system works with the internet as it exists, not as an idealized version of it.

This practical stance is also reflected in how Walrus has been building its ecosystem. Recent integrations and partnerships point toward real-world usage rather than narrow experimentation. The focus has been on improving bandwidth, reducing latency, and supporting real-time data use cases. These are not flashy announcements, but they are telling. They suggest Walrus is positioning itself as a serious data layer that others can build on. Not a side experiment. Not a single-purpose tool. Infrastructure that fades into the background while making more ambitious applications possible.

The best way to describe Walrus today is not as storage, but as coordination around data. It allows large objects to be stored as blobs, keeps them recoverable even when nodes come and go, makes them verifiable enough to be referenced by applications, and serves them fast enough that users do not feel punished for choosing decentralized systems. Each of those pieces exists elsewhere in isolation. Walrus combines them into a coherent layer. That combination is what makes it interesting. It does not try to dominate the narrative. It solves a quiet problem that every serious application eventually runs into.

There are, of course, limits and open questions. Long-term resilience depends on healthy incentives for operators. Deep attacks or extreme network failures still test any distributed system. And building on a specific ecosystem like Sui means inheriting both its strengths and its risks. Walrus does not eliminate these realities. What it does is acknowledge them and design around them thoughtfully. That alone sets it apart in a space that often overpromises and underexplains.

In the end, Walrus made me rethink what storage should mean in Web3. Not a place where files sit untouched. Not a race to see who can replicate the most data. But a living layer that applications can depend on, reason about, and scale with. It is the kind of infrastructure that rarely trends on social feeds, yet quietly shapes what becomes possible. And in a system that wants to support real users and real workloads, that kind of quiet progress may matter more than any headline.