I learned to separate impressive systems from reliable systems later than I would like to admit. Early on, almost everything looks convincing. Clean dashboards, smooth demos, confident metrics. It is only after months of continuous operation that a different signal appears. Not whether something works once, but whether it keeps working the same way when nobody is watching closely.

That difference is where demo AI and running AI split apart.

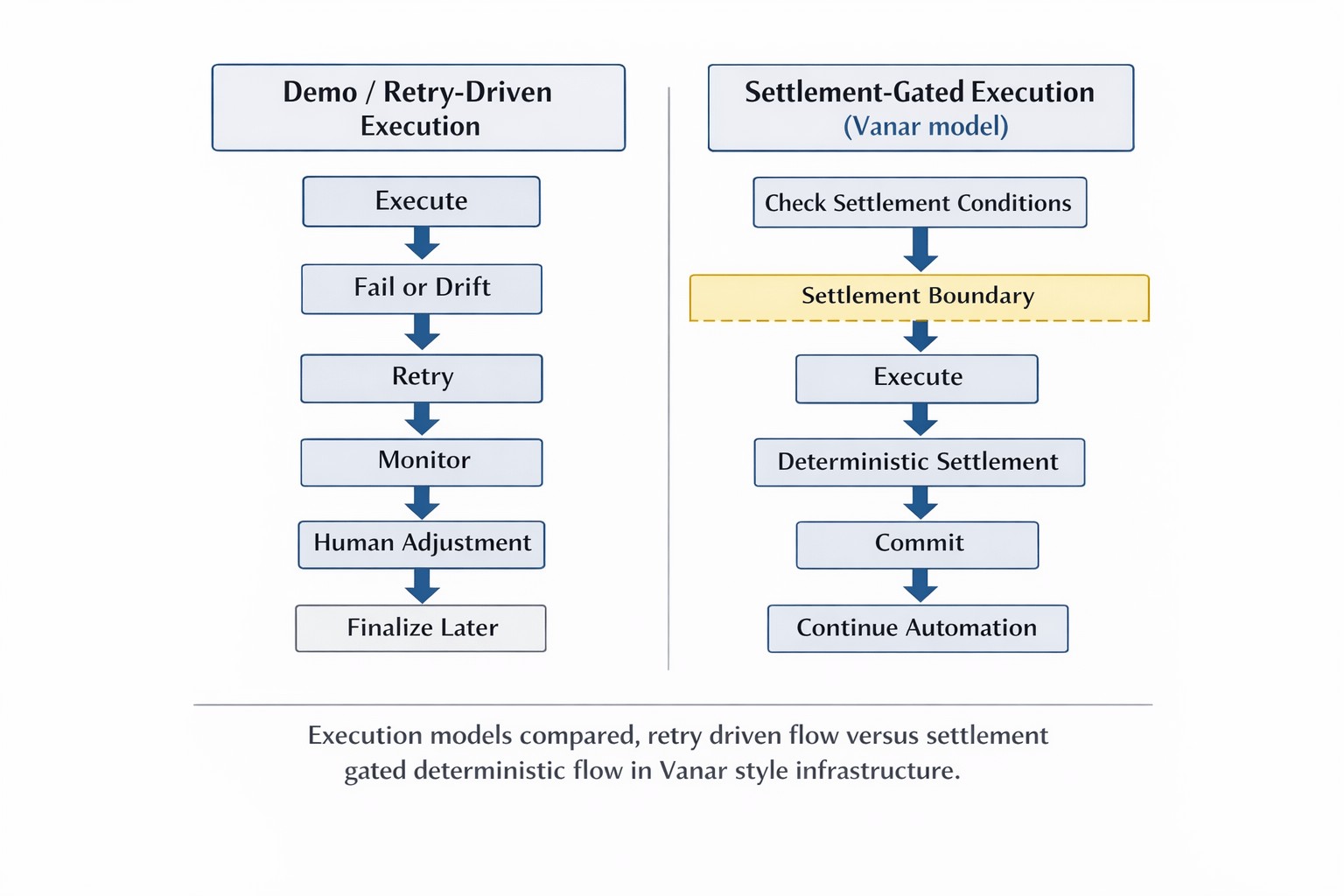

Demo systems are built to prove capability. Running systems are built to survive repetition. In demo environments, failure is cheap. If a transaction stalls, someone resets it. If execution fails, someone retries. If parameters drift, someone adjusts them. The system still looks successful because a human quietly absorbs the instability behind the scenes.

Continuous systems cannot rely on that invisible correction layer. When execution runs nonstop, every retry becomes logic, every exception becomes code, every ambiguity becomes a branch in the state machine. Over time, complexity grows faster than functionality. What breaks is rarely the core algorithm. What breaks is the execution certainty around it.

This is the lens through which Vanar started to make sense to me.

Vanar does not read like infrastructure optimized for first-run performance. It reads like infrastructure optimized for unattended repetition. The difference shows up in how settlement is positioned relative to execution. In many environments, execution comes first and settlement certainty follows later, sometimes with retries, monitoring, and reconciliation layers. That model works when humans supervise the loop. It becomes fragile when agents operate independently.

Vanar appears to invert that order. Execution is gated by settlement conditions rather than patched after the fact. Actions are allowed to proceed when finalization behavior is predictable enough to be assumed. That reduces the number of runtime surprises automation has to absorb. Fewer surprises mean fewer branches. Fewer branches mean lower operational entropy.

I have seen highly adaptable systems age poorly. At first they feel powerful, because they can respond to everything. Later they become harder to reason about, because they respond differently under slightly different stress conditions. Execution paths drift. Ordering shifts. Cost assumptions expire. Stability becomes a moving target rather than a property.

Vanar seems designed with that drift risk in mind.

Settlement is treated less like a confidence slope and more like a boundary condition. Instead of assuming downstream systems will stack confirmations and defensive checks, the design pushes toward a commit point that automation can treat as final without interpretation. That directly changes how upstream logic is written.

Instead of confirmation ladders, you get single commit assumptions. Instead of delayed triggers, you get immediate continuation. Instead of reconciliation trees, you get narrower state transitions.

In day to day operation, I trust compressed state machines more, because they are easier to audit, easier to reason about, and easier to keep stable under automation.

That compression is not free. It comes from constraint. Validator behavior is more tightly bounded. Execution variance is narrower. Settlement expectations are stricter. The system gives up some runtime adaptability in exchange for clearer outcome guarantees. From a demo perspective, that can look restrictive. From a production perspective, it looks deliberate.

There is also an economic layer to this distinction. In many demo style systems, value movement is abstracted, delayed, or simulated. In running systems, value transfer sits directly inside the loop. If settlement is slow or ambiguous, the entire automation chain degrades. Coordination overhead rises. Monitoring load increases. Human escalation paths quietly return.

Vanar’s model pulls settlement into the execution contract itself. An action is not meaningfully complete until value resolution is final and observable. That shared assumption is what allows independent automated actors to coordinate without constant cross-checking. State is not inferred later. It is committed at the boundary.

This is also how I interpret the role of VANRY inside the system. It makes more sense as a usage-anchored execution component within a deterministic settlement environment than as a pure attention asset. The token sits inside repeatable resolution flows, not just at the edge of user activity. Whether markets price that correctly is a separate question, but the architectural intent is clear.

I do not see this design as universally superior. Some environments benefit from maximum flexibility and rapid experimentation. But for long running, agent driven, automation heavy systems, adaptability at the wrong layer becomes a liability. Small deviations do not stay local. They propagate through every dependent step.

Demo systems optimize for proof. Running systems optimize for repeatability. Vanar aligns much more clearly with the second category.

Less impressive on day one. More reliable on day one thousand.