Written by: Raullen Chai, Andrew Law

Compiled by: Shenchao TechFlow

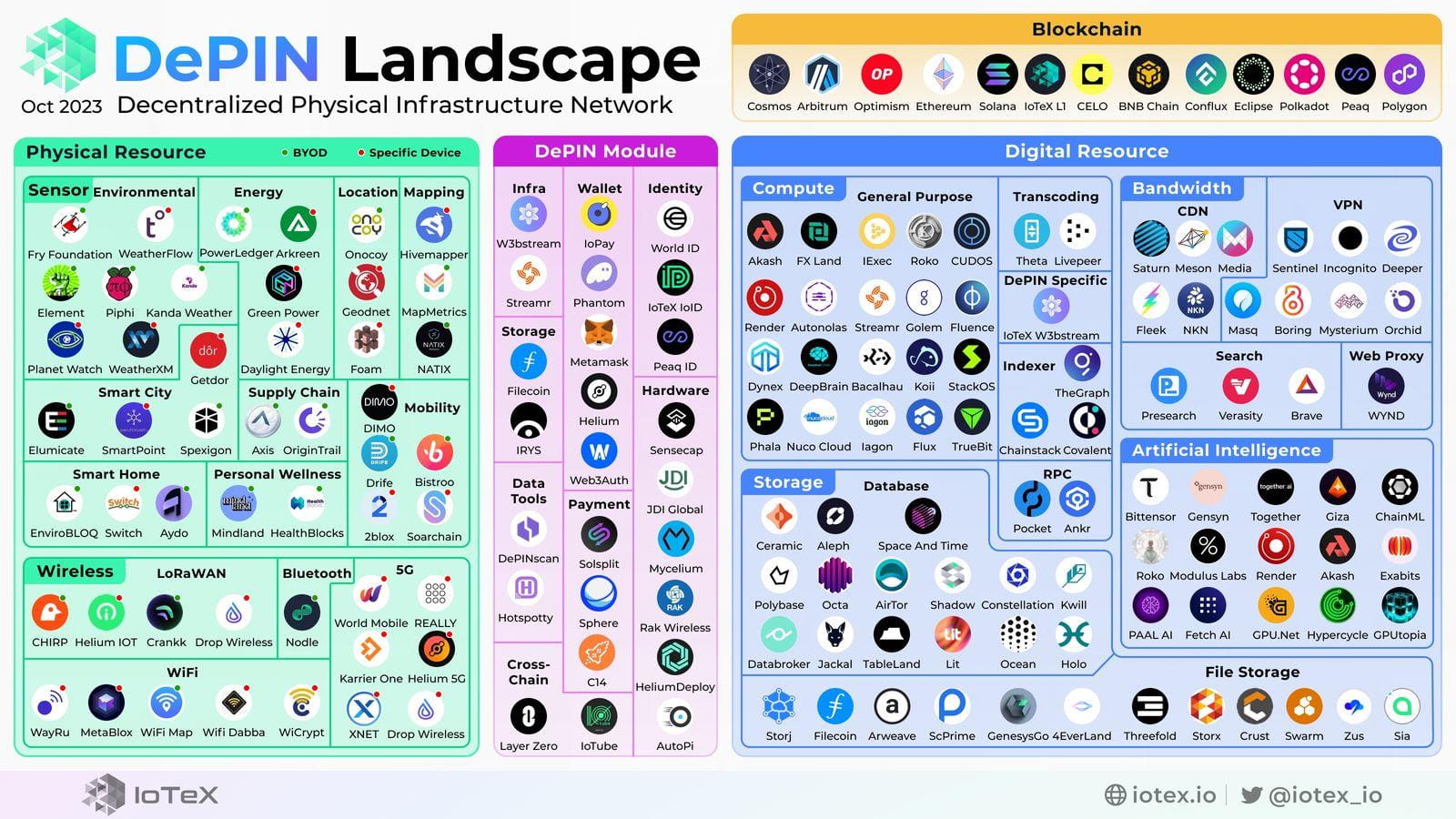

Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks (DePIN) represent a transformational upgrade in the way we plan and organize real-world systems. It spans energy, transportation, telecommunications and other fields. By combining blockchain, cryptocurrencies, and smart contracts with smart devices, DePIN provides the ability to coordinate physical infrastructure in a decentralized and peer-to-peer manner. As a16z’s Guy Woullet points out, the key to DePIN’s success lies in solving a core challenge: ensuring trusted verification of geographically dispersed service nodes without the need for centralized management. This article delves into the problem of decentralized verification in DePIN, critically analyzes existing solutions, and proposes innovative ways to guarantee scalability without compromising security and decentralization.

The rise of DePIN

DePIN leverages the power of blockchain and smart contracts to build open markets for services rooted in physical infrastructure. Imagine an energy-based DePIN: a home equipped with solar panels can potentially produce electricity and deliver surplus power to neighbors. Facilitated by blockchain and executed by smart contracts, these energy transactions can be automatically recorded and settled. At the heart of this process are IoT devices, such as batteries and other microgrid-connected hardware, which make it possible for homes to distribute energy in a trusted, direct, peer-to-peer manner, without the need for power companies as middlemen.

These decentralized physical infrastructure networks will gain increasing traction across industries in 2023. By marginalizing centralized gatekeepers, DePINs promise to increase efficiency, reduce costs, expand accessibility, and empower individuals.

Structure of DePIN

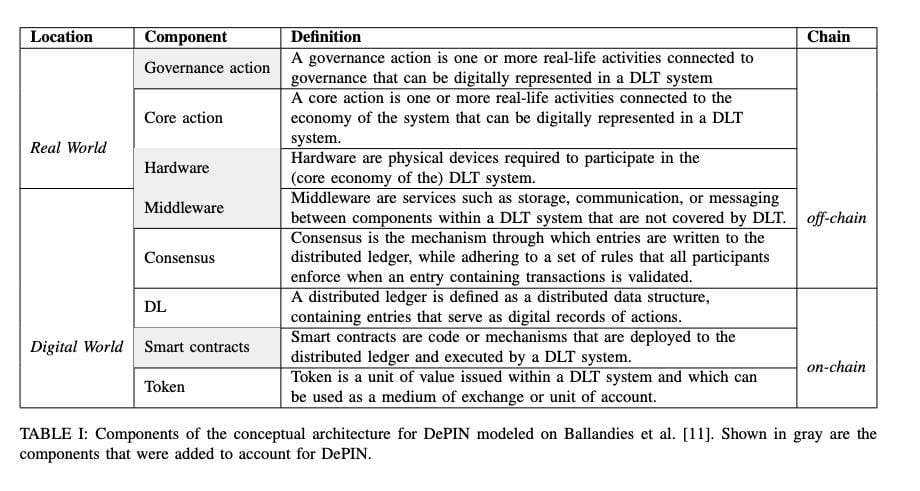

Decentralized physical infrastructure relies on a complex technology stack that brings together hardware, connectivity, middleware, blockchain-based smart contracts, and web or mobile applications.

Zooming in on a typical DePIN network (like DIMO or Helium or WiFimap or GeoDnet), they usually have three roles:

Service Node: A group of servers or devices that provide services or utilities, such as WiFi/5G, environmental data collection, and energy production.

Middleware: A layer that is primarily dedicated to verifying that service nodes are working properly. It ensures accurate representation and reporting of real-world activities and events from service nodes to smart contracts, which may be closely related to how DePIN tokens work.

End-users: Everyday people or business communities that actually use the utilities provided by the service nodes or devices. The middleware is responsible for measuring the quality of service or utility from the nodes by tracking certain metrics, the lack of which may result in:

Self-dealing: Participants may utilize the network by obtaining services using infrastructure they own, thereby accumulating fees and rewards. For example, an energy entity can simulate purchasing energy from its own reserves. Given sufficient subsidies or initial block rewards, self-dealing becomes very profitable.

Lazy providers: Infrastructure providers may promise to provide services but either fail to deliver or provide poor quality services. Without a strict verification system, users have nowhere to complain.

Malicious providers: While less common than the previous two, there is the potential for malicious entities to manipulate the infrastructure to trick users into accepting false sensor data that aligns with the financial interests of the provider. If not controlled, these actions can undermine the economic incentives of DePIN. Trust and network efficiency degrade, leading to a “tragedy of the commons” where providers seek their own interests, or to a centralization of power. In both cases, the goals of a decentralized, peer-to-peer driven infrastructure are undermined.

Authentication Middleware

Designing and architecting such a middleware is very complex. Let's look at it from different perspectives.

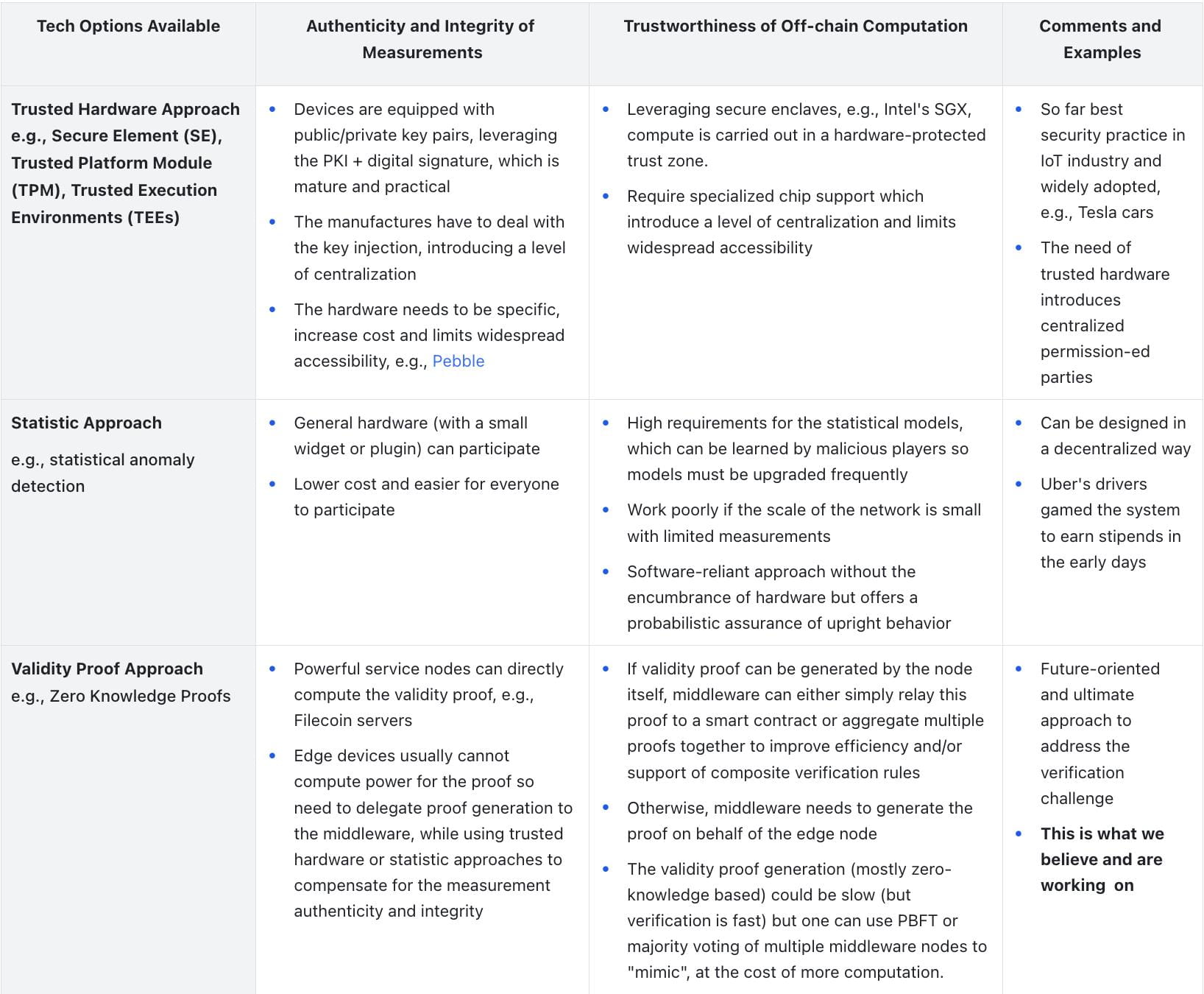

Perspective A: Feasible Verification Technologies

Authentication in DePIN is considered successful if both of the following are achieved:

Authenticity and integrity of measurements: Measurements from service nodes or devices represent their working state (e.g., they have provided a certain service, such as providing WiFi connectivity or collecting environmental data) and must be authentic and untampered.

Trustworthiness of off-chain computation: Often, measurements cannot be used directly for verification purposes. Some amount of off-chain computation needs to be done to process them, which needs to be trustworthy, e.g. not cheatable.

Take an energy-focused DePIN as an example: the smart contract must trust that the smart meter correctly measured solar power generation and that the middleware verified 6 hours of measurements that may have come from this smart meter before it can initiate a cryptocurrency payment on-chain.

To achieve these two points, we can list the currently available technologies as follows:

Perspective B: Packaging and verification technology in a decentralized manner

Now that we have enough knowledge about possible verification techniques, we need to think about how to package them into a protocol in a decentralized way. Here are some ideas:

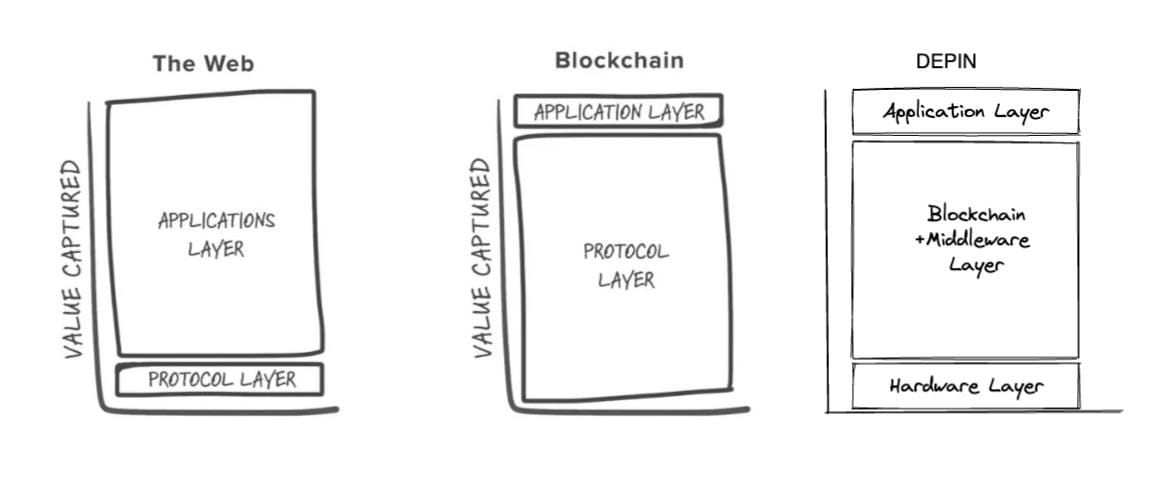

The hardware layer needs to be minimal (to ensure broad accessibility and decentralization) and many functions should be rolled into middleware to help avoid centralization risks in other areas of the stack. This is similar to the famous "fat protocol", we want the hardware layer to be thin, and the middleware to be fat.

The middleware operates similarly to public blockchains in the following ways:

Allows anonymity and neutrality (open source, community-run)

Transparent and trustless, providing high security against sophisticated attacks driven by financial motives

Ability to perform various types of validation for different scenarios, hence the need for built-in programmability (think smart contracts)

Ability to retain necessary functionality from the hardware or application layer when needed.

Angle C: Verification method

In different scenarios, service nodes work differently. For example, in the case of file storage, service nodes are always working (storing what is promised), so they can be sampled and checked, while in the case of DIMO (car data collection), a service node (device installed in the car) uploads measurements every 10 minutes, so all measurements can be verified. Therefore, the middleware has different verification modes to adapt to different DePIN applications:

Data Processor: This is the most common pattern, where the service node or device essentially sends all measurements to the middleware, which verifies and processes them to generate proofs for the smart contract.

Active Integrator: The middleware protocol actively selects a portion of service nodes to query (note that if the middleware protocol is powerful enough, it can "sample" all service nodes). After getting the node's response, it enters data processor mode. The random sampling method used by Filecoin belongs to this category.

Passive Observer: This is the least common approach, where the middleware just quietly observes the nodes in the service and tries to find evidence that they are (not) doing what they are expected to do (see Dark Forest Theory).

Building W3bstream as middleware for DePIN authentication

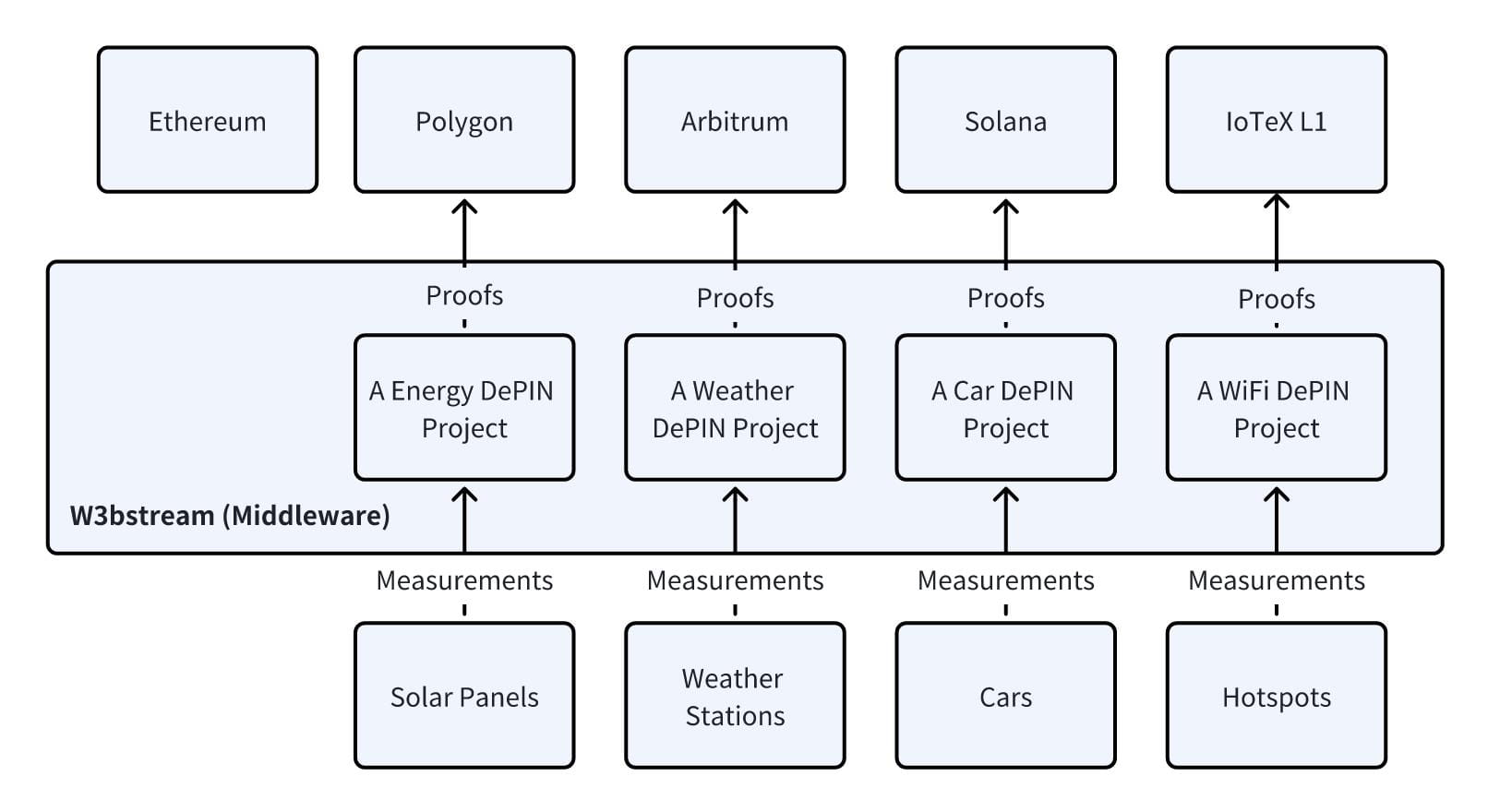

Combining all the above perspectives, we advocate a validity proof-based approach and envision a decentralized, shared, and neutral off-chain verification protocol (as part of the IoT network) serving the DePIN network. This protocol aggregates measurements from a large number of smaller DePIN networks and provides validity proofs for smart contracts (for example, we currently use SNARK proofs).

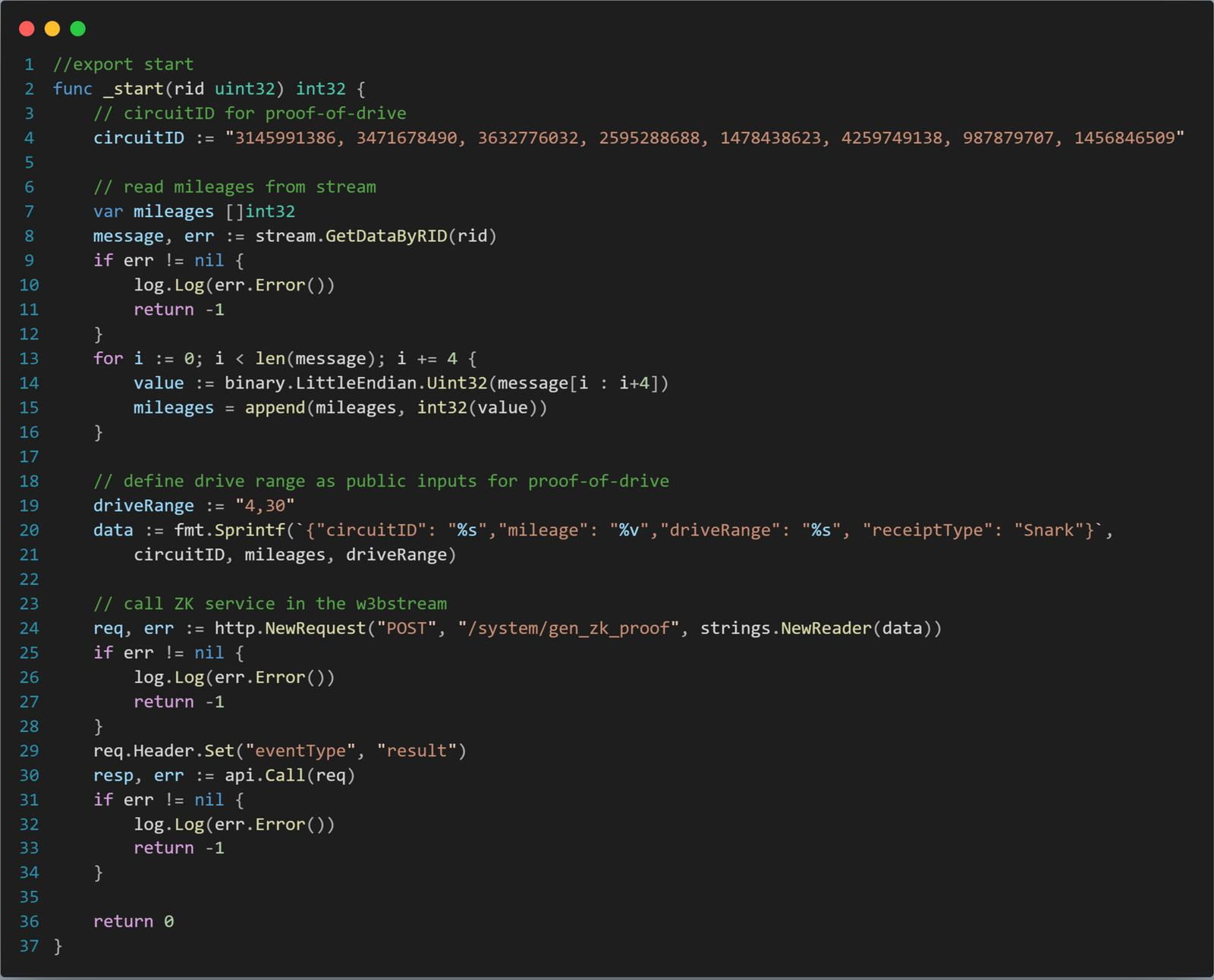

At a broader level, W3bstream is a community-run sharding network that makes it easy for various DePIN projects to deploy (and subsequently update) their verification "formulas" to the platform. These "formulas" can be written in languages such as Rust, Golang, C++, and more will be supported soon. They usually look like this:

Zero-knowledge proofs often come with performance tradeoffs, including longer proof generation times and more computational resources, which makes them less scalable for some real-world applications. We have made internal optimizations (including batching) on top of zk-SNARKs to address these performance issues, with the goal of providing faster proof generation while retaining the core benefits of zero-knowledge protocols.

Decentralized physical infrastructure is on the verge of reshaping our world on multiple levels. However, the key to realizing its full potential lies in solving the challenge of decentralized verification and ensuring the sanctity and inviolability of these networks. We look forward to engaging with top researchers and engineers in the fields of blockchain, cryptography, IoT, security/privacy, and economics to realize this shared vision.