Original title: An Incomplete Primer on Intents

Written by: 0xemperor.eth

Compiled by: Qianwen, ChainCatcher

Intent has become popular in recent research and discussions in the field of encryption, and various protocols are using this concept, such as Anoma, Essential and other protocols are drawing on this concept.

This article aims to provide an initial introduction to the various viewpoints and finally present the appearance of intent resolution architecture when intent is expressed in natural language. If the concept of intent is successful, it has the potential to revolutionize application architecture at all levels.

What is the intention?

Intent allows users to specify certain transaction conditions or preferences without providing exact message calls, thereby increasing flexibility and reducing on-chain complexity.

In the article "Intent-based Architecture and Its Risks", the definition of intent is: an intent is a set of declarative restrictions that allow users to outsource transaction creation to a third party without giving up full control over the transaction parties.

In a podcast, Chris Goes from Anoma defines it in two ways: intent refers to "a credible commitment to a preference for certain system states" and "a credible commitment to limits on information flows."

An intuitive way to think about intent is that it basically represents a desired outcome. When you express an intent, you are only defining the outcome you want, not the process to achieve your goal.

For example, if you want to exchange Tether (USDT) for ETH, then instead of managing the entire process yourself - choosing an exchange, setting up an account/signing transactions, handling transfers (or cleaning up crypto dust in your wallet), etc., you can simply submit an intent stating that I want to exchange 1 ETH for 2000 USDT. Another entity (called a Solver) will take your intent and figure out how to make it happen. The Solver handles the messy details and strives to optimize the best outcome for you.

The key point is that intent focuses on outcomes rather than processes. Users define the desired outcomes, and others take care of the process to achieve them. Intents allow you to specify the outcome without worrying about the steps, greatly simplifying the transaction process that most users use in cryptocurrency.

The higher-level idea is that users can define what they want without specifying which contracts they want to start trading from (we can call this a calculation path or simply a transaction path). Users can also restrict this by indicating that they prefer certain paths or contracts.

Example

Cowswap

Cowswap uses batch auctions as its core price discovery mechanism. Instead of executing trades immediately like AMMs, Cowswap aggregates orders off-chain and settles them in batches. This allows a unified settlement price to be determined for all trades in a batch, eliminating problems such as front-running that are common in instant execution. Batch auctions also optimize gas fees by settling many trades at the same time. Solvers compete openly to submit order settlement solutions to ensure that the parties to each batch of trades can maximize their interests. The best solution determines the final unified price. Overall, batch auctions achieve fairness, efficiency, and MEV protection, which cannot be achieved in the instant execution model.

A key innovation of Cowswap’s batch auction model is the ability to find coincidences of wants (CoW) between orders. CoW is a direct peer-to-peer settlement between trades with mutually beneficial wants. This liquidity sharing means that no external liquidity providers are required to facilitate these trades. CoW can also include multiple assets in ring trades at the same time. By maximizing the use of CoW, batch auctions can access more liquidity than isolated pools. Settlements will utilize CoW where permitted, and the rest will be executed through on-chain liquidity. Combining batch auctions with CoW liquidity sharing can provide traders with better pricing and execution.

The CoWswap model is similar to the intent model, where users express their trading intentions in the form of limit orders, which are entered into the order book. Solver uses the order book state to match them in the form of ring transactions or route them through AMM (i.e., users only mention the price, not the calculation path or the specific location where they want to execute).

Uniswap X

Uniswap X

The Uniswap X paper proposes a decentralized trading protocol that uses signed off-chain orders and settles on-chain through Dutch auctions. Users sign orders, specifying parameters such as input/output tokens, quantities, and price limits. These orders are distributed to "fillers" who compete for the best execution price.

Uniswap X proposes setting the initial Dutch auction price through an off-chain inquiry system. Users can ask the network of fillers for prices, and provide a short exclusivity period for the best offer to incentivize honest pricing, after which the order enters the public Dutch auction.

Similarities between Uniswap X and Cowswap

Both use off-chain signed orders that are aggregated and settled in batches on-chain. This can save gas fees compared to on-chain orders.

Both aim to promote competition among liquidity providers to find the best execution price (liquidity providers are called Solvers in cowswap and Fillers in uniswapX).

Cowswap emphasizes the use of CoW to facilitate direct peer-to-peer transactions, while Uniswap X focuses more on integrating off-chain and on-chain liquidity sources.

The RFQ (request for quotation) system in Uniswap X and the signing model (users express their intent and then let other users fill orders) are similar to the intent architecture.

Formal Definition of Intent

Users simply express their intent, such as “I want to exchange X asset for Y asset,” and the Solver figures out how to best implement that intent and handles all the blockchain-related details behind the scenes. The Solver gives proof that the intent was fulfilled and can participate in mechanisms such as auctions to fulfill the intent in a decentralized manner.

This blog explores some definitions:

First model: an intent i is defined as a tuple (B,E,T) :

B represents the set of supported "start" states.

E represents the set of supported "end" states.

T is a set of preferred transaction sequences.

The state transition function s: Q×T → T moves from the starting state to the ending state through a series of transactions t.

An intention is considered fulfilled if it starts in state q0∈B and ends in state qn∈E via a sequence of transactions t∈T.

Intent clearing: If the sets B, E, T have a non-empty intersection, then a set of intents to, …, tm can be cleared, allowing the creation of a meta-intent t’ using these intersections.

As we mentioned earlier, intents are issued by users and then solved by Solvers; regardless of the format in which it is expressed, intents are an optimization problem for Solvers. In layman's terms, a user might state an intent like "I want to buy 4 ETH worth of BTC" and the Solver will usually find a place to fill or exchange this order. But intents don't stop there; they also allow for the addition of constraints like "lowest possible slippage" and "not trading on a DEX that prohibits US users from trading", which in turn become additional constraints that the Solver must keep in mind.

Challenges include:

The expression of intent needs to be simplified.

Certain intentions may have an impact on user welfare, such as zero slippage in DEX.

Execution tracking may require attention due to risk or legal reasons.

The goal is to strike a balance between clearly capturing user intent preferences and practical considerations of computational efficiency and user experience.

A Lagrangian interpretation of intent search is also mentioned here.

To me, the intent statement looks like a Markov Decision Process. However, a Markov Decision Process has random state transitions, whereas this would be a deterministic MDP with absolute state transition values, which can be solved using value iteration, policy iteration, or MCTS (Monte Carlo Tree Search) (the last one is also used to solve the Go part of AlphaGo).

Intent drives user experience

Intents are likely the next stage in the evolution of on-chain UX. The way UX works on-chain right now is primarily around the transactional level, where users sign off on every transaction as part of the operation. So every step on-chain is expressed through a transaction. In very simple terms, intents are meta-transactions where the activity is expressed at a very abstract level, and it’s up to the Solver to do their best to satisfy the user’s intent. This might include buying some ETH for X price, wanting to get the best deal possible, which can be done either as a single huge swap on Uniswap on Ethereum, or sharding it on a roll-up and then buying ETH (counting fees as well).

Currently a simple swap from USDC to ETH involves the user approving a limit on the token, approving the token type, and then approving the trade, whereas in an intent-centric world, the user is abstracted from these details and only needs to perform the action they are interested in. There is an unofficial rule in web design that no action should be more than three clicks; currently if a user wants to do a swap, they must simultaneously select the token, and perhaps adjust slippage and trade, which may not seem like a lot of work for a single transaction, but can be a cumbersome user experience when repeated multiple times.

Unibot shows the pattern of intent-based architecture in a very basic way. It removes the complexity from trading, providing traders with a simple and easy-to-use user experience, but with some limitations on possible flexibility. Despite the app's alleged risks with key handling, which could lead to attacks, it still has a stable user base despite charging taxes, which shows that there are still untapped opportunities in the user experience in the cryptocurrency world.

Conversational Intent Flow

How does AI fit in in an intent-centric blockchain world? The concept of intent recognition has been around for decades in the field of natural language processing and has been heavily studied in conversations. For example, imagine a user visits a travel website and has a conversation with a chatbot; initially, the intent might be to book a flight or check a reservation or status, and the user provides various details. If booking a flight, the user needs to provide the destination, time, date, and class of flight they are interested in; in some cases, the user might also need to select an airport. In this example, the user's intent is the intent of the conversation, and the various details the user provides are the spaces/slots that need to be filled in to fulfill that intent.

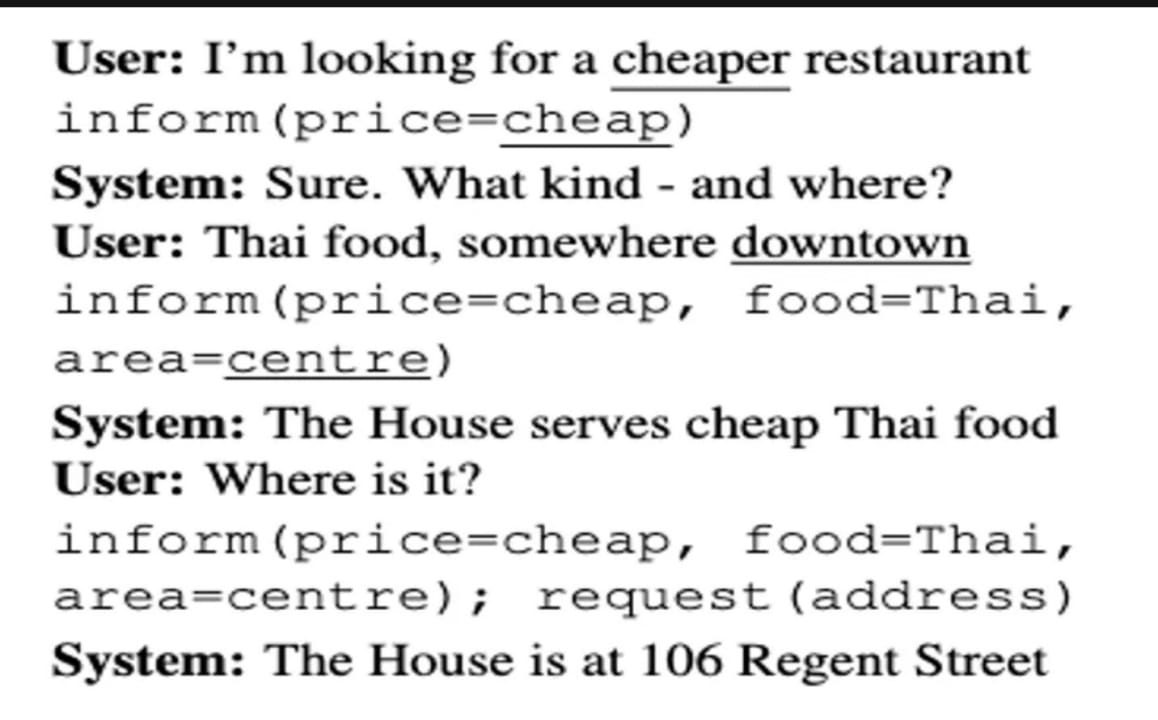

Annotated conversation status in a conversation

Annotated conversation status in a conversation

Another example of intent recognition and detail filling is when you intend to play a song, various spaces (details) related to the song appear in the sentence, such as the song name and the artist who sang the song.

Intent classification and gap filling is a very complex problem in the conversational world because you can have conversations that span multiple turns, sometimes have global intents and local intents, and you have to keep track of a lot of state. Every time you use Siri and Google Assistant to schedule an alarm or record something in your calendar or birthday, there is some level of intent classification and gap filling behind it.

How does this relate to blockchain? As we move from a transaction-centric world to an intent-centric world, the details of how we get from intent to transaction have not yet emerged in the popular discussion. The interface between the intent pool and the memory pool does not exist. Accessing on-chain models and using them for intent recognition and space filling provides a natural language interface (the most natural interface, in my opinion) to the intent pool and solver.

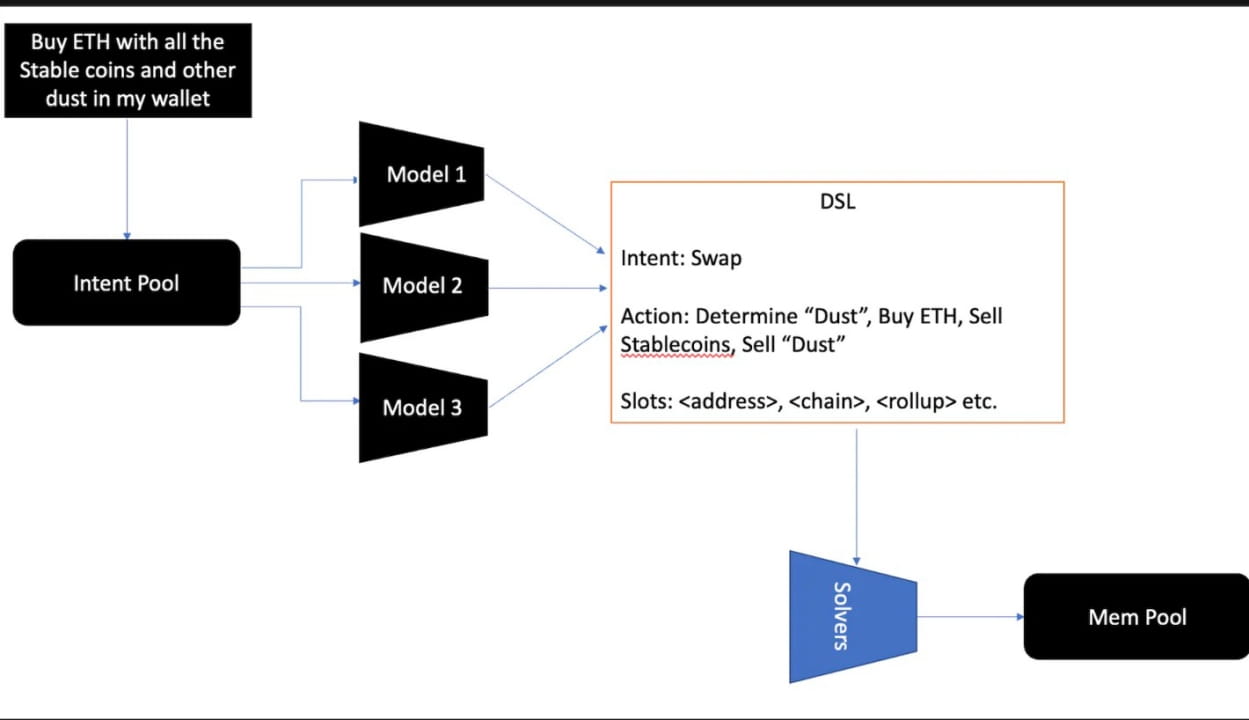

The general idea is to access a set of models on a chain, reducing each intent to a DSL (domain-specific language); this domain-specific language will include details such as the core intent (buy, sell, bridge, borrow/loan), and other details such as address, size, slippage preference, etc. (depending on the intent type). The global DSL allows anyone to deploy a model, simplifying the intent to a specific DSL. In the case of multiple such models, the model voted in the model collection will be taken.

The availability of on-chain models helps us develop this interface securely and provably, with proof of computation for each intent/solution being provable. In some cases, capturing the results of majority votes of various models may give us insight into how intents are chosen, and in some isolated cases, even help solvers solve these intents better.

The on-chain model used here can be a standard deep learning model like BERT, which is trained for this purpose, or a large language model inference used in an ensemble; this detail may be up to different participants or solvers. In the case of an encrypted intent pool, we need to use homomorphic encryption or private inference methods to ensure data privacy while being able to compute on it. Every epoch, or every few epochs, a proof can be published on-chain where the model is the validator. The validator can be a human or another model that publishes a statement about the validity of the model. This last part of the process ensures that the lifecycle of the model is taken into account, whether the model can accurately handle the intent or not. Sometimes, when the validator is a mature participant, that participant may discover flaws in the model that can be quickly addressed and replaced with a newer model.

As shown in the figure below, for the action/thought of "make a purchase with stablecoins and dust in my wallet", once it enters the intent pool, it goes through various models and is parsed into a DSL with various details such as intent, sub-actions, and details that need to be filled in. The parsing of the DSL can be as detailed or as abstract as possible; the intent conversation may last for several rounds because the threshold of dust may need to be determined. Once the DSL is in place, the Solver can choose the best path to convert these balances into ETH and then pass the transaction to the memory pool.

Intention Resolution Model Example Another DSL Architecture - Essential

Intention Resolution Model Example Another DSL Architecture - Essential

Account abstraction turns all accounts into smart contracts, separating accounts from signers in Ethereum. This allows accounts to customize different authorization logic based on user needs. However, achieving complete account abstraction requires major adjustments to Ethereum's core protocol.

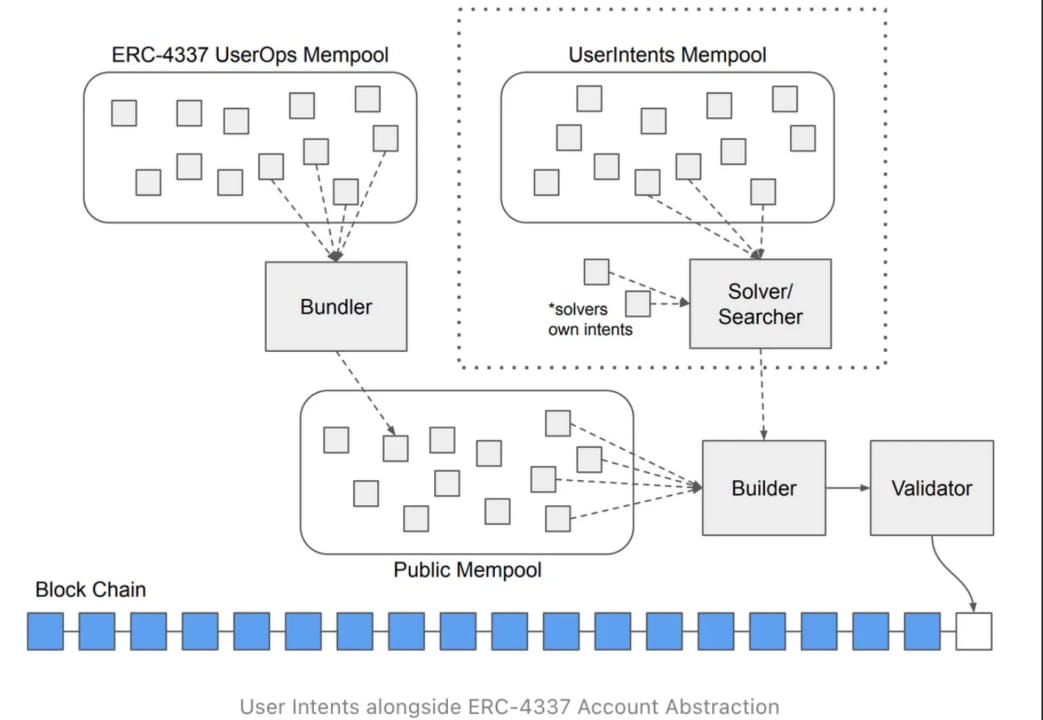

EIP 4337 takes a different approach, achieving the benefits of account abstraction without changing the consensus layer. It introduces "user actions" - pseudo-transactions submitted to the alternate memory pool and bundled by a "bundler" into a transaction that calls the EntryPoint smart contract.

This enables features like social recovery, paying fees in any token, and batching transactions. Developers can set up custom accounts to suit different use cases. By avoiding protocol changes, EIP 4337 can bring these benefits to Ethereum faster. However, it also introduces new complexity and actors, such as bundlers and payers. The resulting dynamics between multiple memory pools, incentives, and transparency will require careful management.

Intents allow users to specify a desired outcome rather than a specific action. Solvers then help users achieve that outcome in the best way possible. However, current implementations are limited, exhibiting centralization, lack of composability, and insufficient competition between solvers.

An EIP proposed by Essential will change this. Account abstraction through initiatives such as EIP 4337 will enable smart contract-based accounts instead of traditional Externally Owned Accounts (EOA). This will allow users to submit general intents instead of pure transactions. Intents represent the desired results of users and can be supplemented by Solvers to maximize participant satisfaction.

EIP 7521 proposes a framework to support evolving intent standards without the need to continually upgrade smart contract wallets. Users sign a "user intent" that specifies which "intent standard" contract will handle the intent. These intents are submitted to the EntryPoint contract, which handles signature verification as in EIP 4337. The user intent memory pool exists simultaneously with the ERC 4337 memory pool, and the Solver handles the intent.

ERC-4337 User Intention Anoma under Account Abstraction

ERC-4337 User Intention Anoma under Account Abstraction

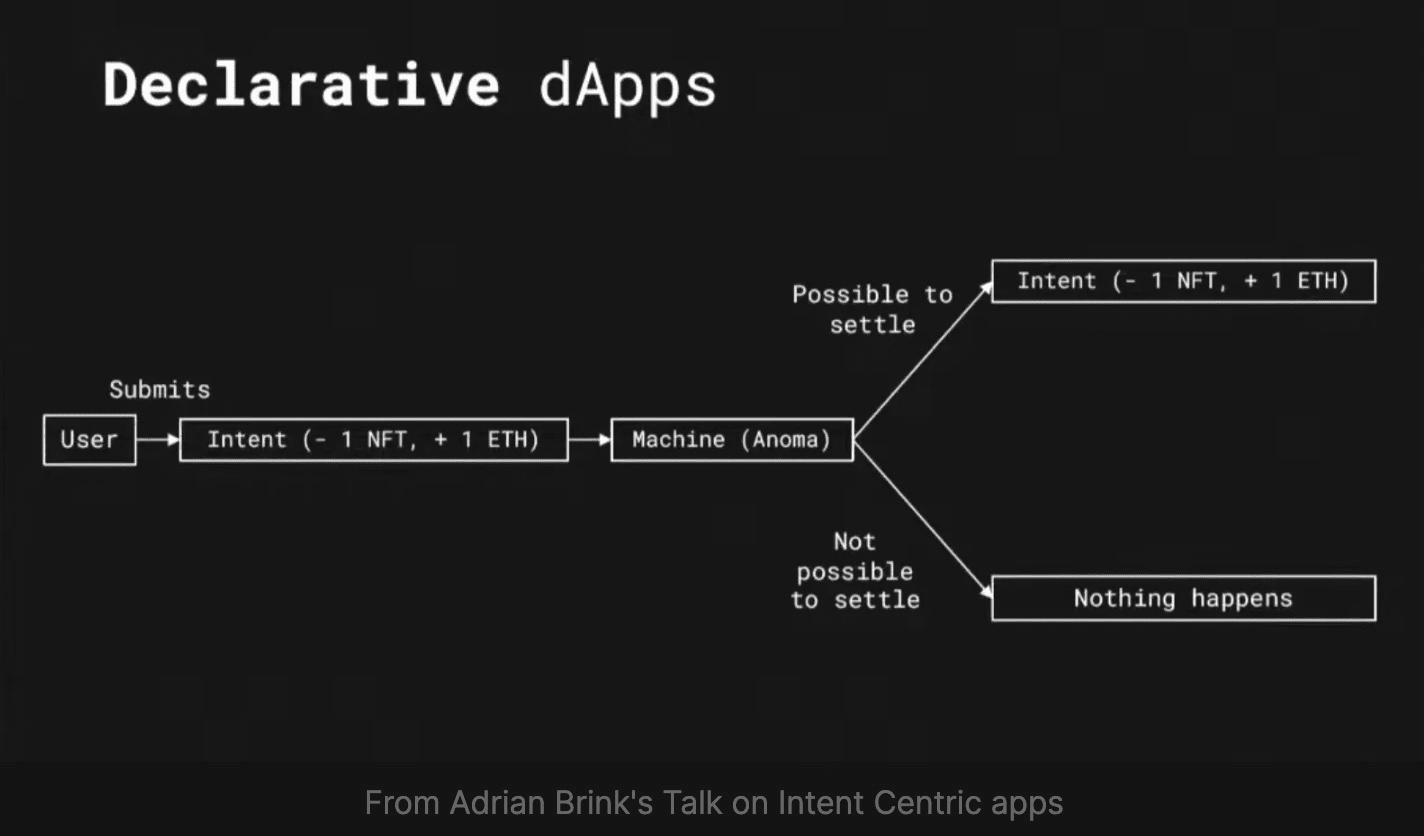

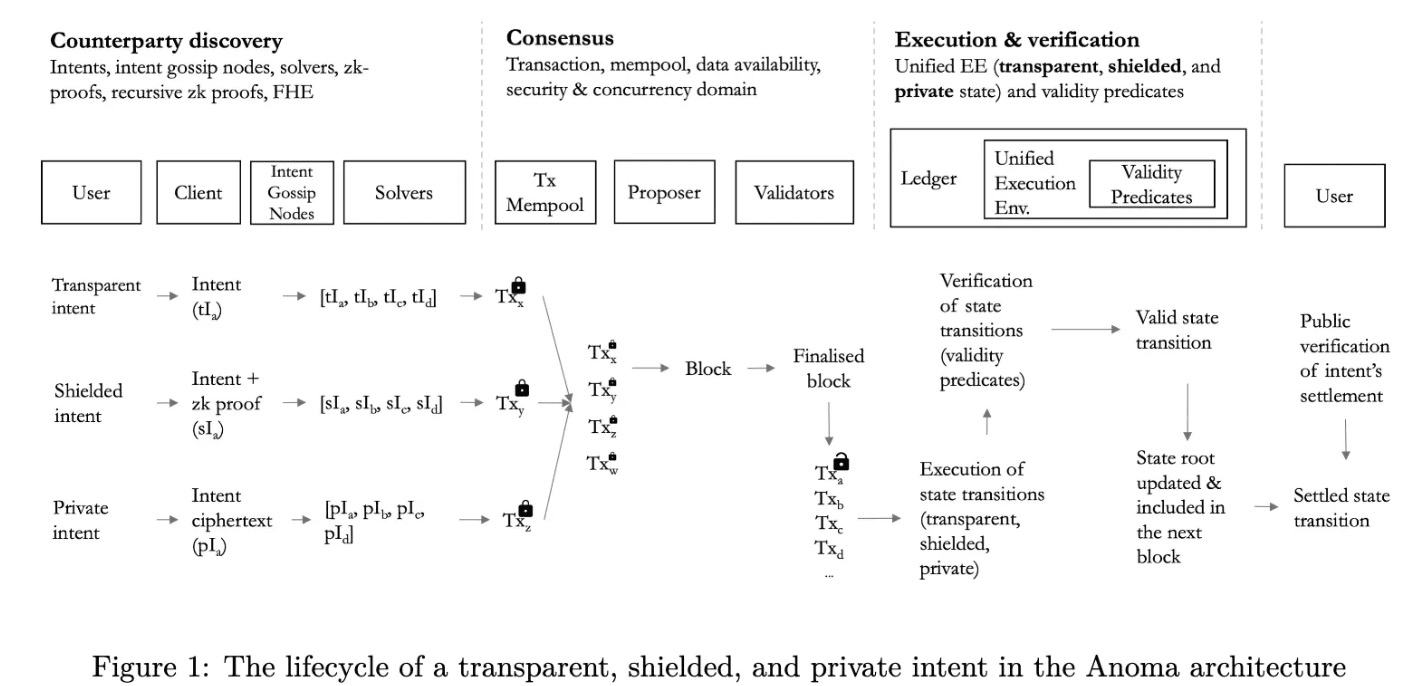

Anoma is an intent-centric architecture that centers on building the infrastructure layer around programmatic intent rather than transactions. Intents are partial state changes signed by users expressing preferences rather than full state change transactions. This intent-centric design enables decentralized counterparty discovery and resolution. Anoma is attempting to move from an imperative paradigm to an imperative paradigm.

Excerpt from Adrian Brink’s talk on intent-centric apps

Excerpt from Adrian Brink’s talk on intent-centric apps

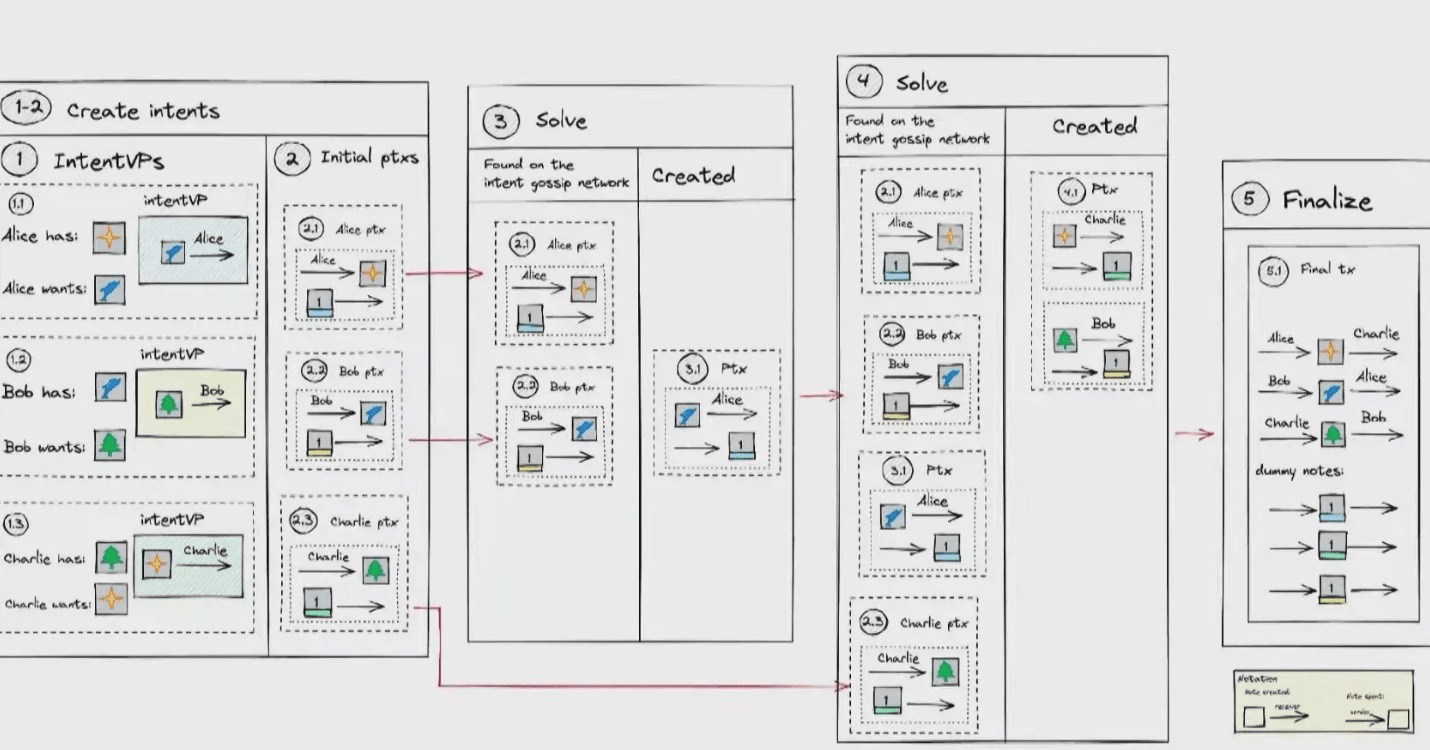

Users broadcast intents, which propagate across the intent gossip network. Different nodes can specialize in certain intents based on their computational resources and the types of intents they want to serve. Solvers observe intents and attempt to combine compatible intents into valid transactions that can be settled on-chain. Transactions are submitted to an encrypted memory pool using threshold cryptography, so front-running is impossible. Anoma also has a partial intent model that allows for intent combination.

Chris speaks on Intent x Rollup - Anoma Partial Intent Model

Chris speaks on Intent x Rollup - Anoma Partial Intent Model

Anoma's focus on privacy is on "user-level choice", that is, giving users the flexibility to disclose their intention information and choose what to disclose.

The architecture consists of multiple components. The Tiger execution engine uses ZKP and homomorphic encryption to process transparent, protected private data. Typhon is the consensus algorithm. The compiler stack includes the Juvix language, AnomaVM, and VampIR.

The architecture has a homogeneous protocol and a heterogeneous security model. It can be deployed as a standalone blockchain or used as a ZK roll-up or decentralized order book to achieve decentralized distribution of applications on Ethereum. Users with different security requirements can leverage the same protocol while making security trade-offs based on their needs.

Anoma makes it easier to build decentralized applications compared to the transaction-centric model. Intents enable new applications such as rollups, multi-barter transactions, and private DAOs. In summary, Anoma provides a flexible and modular architecture that meets the requirements of contemporary decentralized applications. It focuses on intents rather than transactions, solving the problems of counterparty discovery and coordination while preserving privacy.

Anoma has a unique design philosophy that views intent as "information flow" and "restricted/private information flow", and makes architectural and design choices based on this. This also illustrates the fact that Anoma's intent composition model leads to generalized intent models that may be technically difficult to solve under privacy constraints because efficiency trade-offs limit the amount of information that can be kept confidential.

summary

Intent as a research and engineering problem is currently a very interesting area in cryptography.

Open questions that need to be addressed in the field of intent:

Formal Definition of Intent

What does an intent-centric application architecture look like beyond DEX?

When solving any optimization problem, designing the trade-off between privacy and utility requires obtaining as much information as possible. If the intention of privacy is to be achieved, a certain amount of information must be disclosed to solve the intention problem.

What is the most basic knowledge needed to solve the intention problem?

If you were to cut off access to other knowledge, what would the trade-offs be?

How to express this privacy-efficiency trade-off in a common way.

Generic intents can be too large to be solved, and for a state space as large as Ethereum, this becomes an intractable problem. This suggests that it is best to have some constraints on solving the intent problem, and also be limited when trying to combine intents (when there are common intents). In my opinion, generic intents are extremely difficult to achieve in practice, and intent-centric architectures will be inherently application-specific.

While these are research questions, design choices to implement intent also create various engineering problems. It can lead to over-reliance on (permissioned) middlemen, which can lead to infrastructure concentration in different stacks (in the case of UniswapX, 77% of trading volume is off-chain inventory filling). It also entrenches the position of trusted middlemen, raising barriers to participation and stifling innovation, as has already been seen in MEV. The design of any intent protocol must strike a balance between permissionlessness, privacy, transparency, and decentralization.