Original source: Anders Elowsson, Ethereum researcher

Original translation: TechFlow

introduce

I think it is very important to achieve the "Minimum Viable Issuance" (MVI), which is an important commitment to ordinary Ethereum users. Staking should be able to ensure the security of Ethereum, rather than becoming an inflation tax that reduces utility and liquidity and creates oligopoly risks.

Ethereum is evolving and may one day power the global financial system. We have to assume that the “average user” will know about the inner workings of Ethereum about the same as the average person knows about the current financial system.

Of course, we cannot assume that the average user will be driven by some ideology, as was the case with Ethereum’s initial creation. Our job is to ensure that the right incentives are in place so that Ethereum can grow unhindered.

An important design principle that has existed since the birth of Ethereum is the "minimum viable issuance" (MVI), that is, the amount of ETH issued by the protocol should not exceed the amount strictly required for security. This principle is reasonable whether under proof of work (PoW) or proof of stake (PoS).

Under PoW, the role of MVI is to prevent miners from charging too much inflation tax to ordinary users. Therefore, the block reward was reduced from 5 ETH to 3 ETH and finally to 2 ETH.

Under PoS, the MVI principle should also be upheld, and ordinary users should not be charged excessive inflation taxes. Ordinary users should not need to worry about the details of staking to avoid erosion of their savings, or support a set of validators that may be censored, etc.

So, MVI is really about being able to keep the collateralization ratio (the fraction of all ETH used for staking) high enough, but no higher. In this article, I will try to explain why issuing more than the "minimum viable amount" will reduce the utility of Ethereum.

Benefits of MVI for User Empowerment

For individuals, participating in staking has various opportunity costs. It requires resources, focus, and technical knowledge, or requires trust in a third party, and also reduces liquidity. Liquidity staking tokens (LST) are not as reliable as native tokens, nor as suitable as native tokens as currency or collateral.

Therefore, individuals want to be able to earn a return on their stake. Define their minimum expected rate of return as the minimum rate of return they are willing to earn by staking (using their optimal staking method). The (inverse) supply curve for Ethereum is then derived from the minimum expected rate of return for future Ether holders.

The reserve yield for holders can be described as the “indifference point”, where the utility they get from staking is equivalent to not staking. This means that lowering issuance can actually improve utility for everyone, even stakers, as long as Ethereum remains reliably secure.

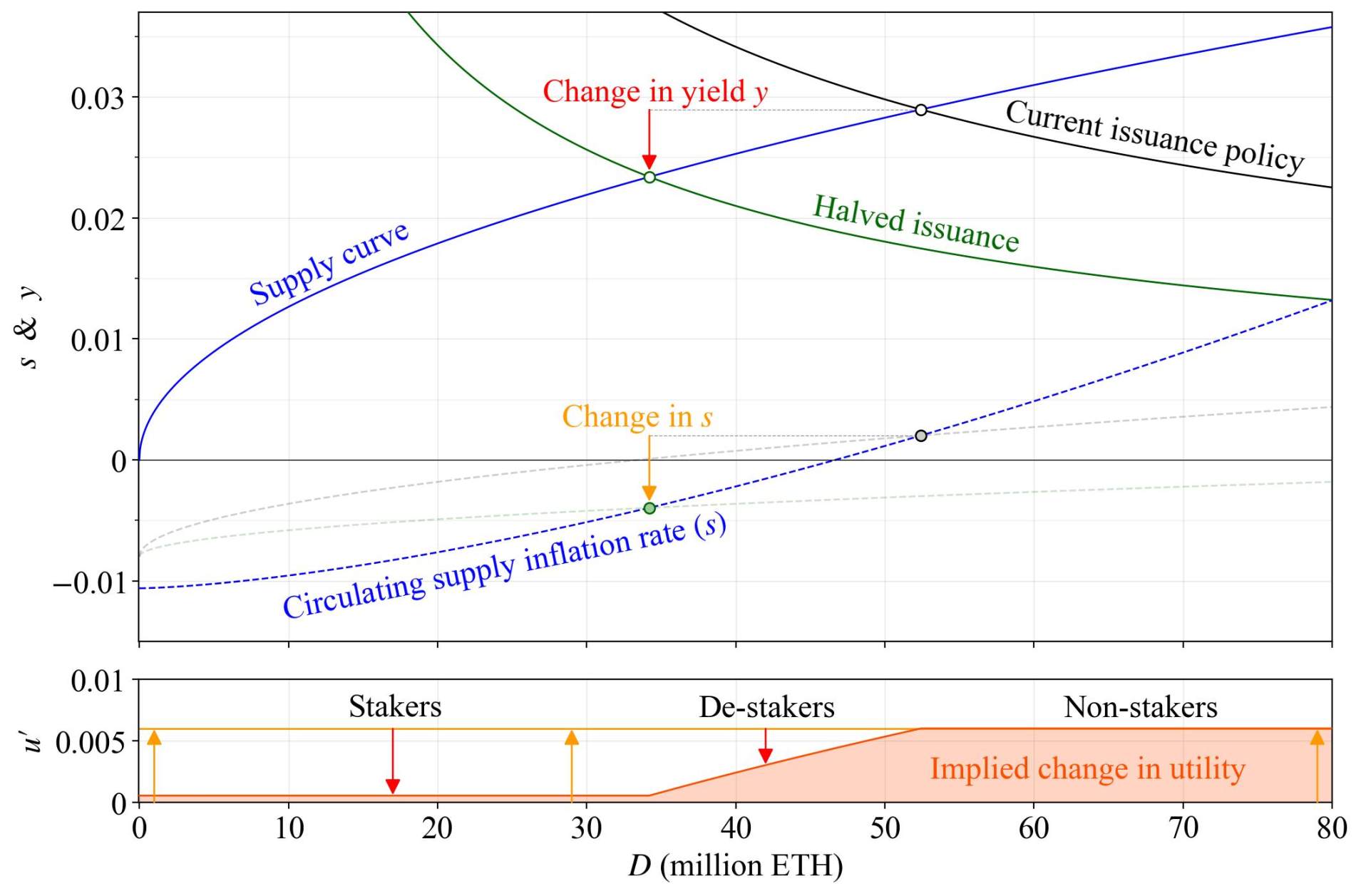

Consider a hypothetical supply curve (blue) with a supply yield elasticity of 2. In this example, I set it to 2% when the stake amount D reaches 25 million ETH, that is, the minimum expected yield of the marginal staker is 2% when staking 25 million ETH.

The real supply curve is a fairly complex phenomenon, and we have not yet reached an equilibrium point where we can anchor its position, but we will start with this simple and fairly realistic scenario. We will also ignore the complexities of compound interest.

The burn rate b is set to 0.008. This is the amount of ETH burned as a percentage of total supply expressed as an annualized ratio since the merger. But this is not the key point, because we are interested in the shift in supply and demand between the medium-term equilibrium points (circles), not the drift in the total ETH supply.

Realized Extracted Value (REV) (a little over 300k ETH per year) has been added to protocol issuance to form the black demand curve (current policy) and the green demand curve (issuance halved by reducing the base reward factor F from 64 to 32).

Halving issuance reduces the yield y (red arrow). This reduces the issuance yield yi=y-yv (where yv is the yield from REV), which reduces issuance i=yid and the circulating supply inflation rate s=i-b (orange arrow).

In one year, the change in the proportion of circulating ETH holdings that someone can obtain, P, depends on s and the rate of return y of each holder, according to the formula: P= 1+y/1+s-1

The current issuance policy gives P 1, and halving the issuance gives P 2, so their proportional relationship is: P = 1 + P 2 / 1 + P 1-1

Define the relevant change in utility as u=P, but use the lowest expected rate of return for those who stop staking when calculating P 2. Below that rate they would not have staked anyway, so they suffer no additional utility loss as their returns fall further.

By this definition, everyone gets higher utility at the new equilibrium. Stakers see a decrease in returns, but a larger decrease in supply inflation, which allows them to earn a larger percentage of ETH.

Of course, non-stakers are clearly better off, since the only change for them is that less ETH is issued to stakers. People who stop staking are the only parties who receive a reduced percentage of circulating ETH at the new equilibrium.

Despite the friction, they are still implicitly better off due to the increase in utility. For example, marginal stakers at the old equilibrium simply didn’t care about staking anyway, so could stop staking and get the full utility improvement from the supply deflation.

When people stop staking, they find themselves somewhere in between, still benefiting from the lower inflation, but suffering some loss in yield, until they become indifferent about staking and unstaking. We have shown that issuance policy is not a zero-sum game from a utility perspective.

Furthermore, any increase in utility gained by any one group will also generally benefit all token holders.

Everyone can benefit from MVI as long as they own the underlying ETH. This excludes CEXs and other staking service providers (SSPs) that profit from staking fees. They do not benefit from the reduction in supply inflation and want to maintain high yields to keep the cut high.

But issuance above the MVI forces unwilling stakers to suffer reduced utility when staking, or to suffer reduced economic consequences when not staking. Under realistic supply curves, even willing stakers are worse off. Note that this example doesn’t even consider tax effects.

A PoS cryptocurrency with a 5% yield, where everyone stakes and the average tax on the staking yield is 20%, would pay 1% of its market cap in taxes every year. This is higher than the amount that Bitcoin will dissipate to miners after the next halving.

The debate does not necessarily depend on how users feel about tax levels or how to interpret staking returns. We can still conclude that by enforcing MVI, Ethereum remains more neutral with respect to differences in tax policies between nation-states.

Arguably, proof of stake requires lower rewards to achieve the same level of security as proof of work, and it is important to take advantage of this to maximize user utility. For example, with a 2% yield and staking 25 million, the total reward is Y=0.022500 = 500,000 ETH.

The "return" to maintaining this solid security is about r=Y/S= 0.4% , which is surprisingly low. We take full advantage of this to maximize utility for users. The potential equilibrium with the current issuance policy is represented by the black circle.

With a yield of about 3% and 50 million ETH staked, that’s Y = 1.5 million ETH/year. The difference in rewards of 1 million ETH per year (over $1 billion at current token prices) can be rewarded to Ethereum users in a way that does not dilute token holders.

For MVI, extracting an average of 15% in staking fees would provide CEXs and SSPs with about $250 million in excess profits per year. Some would be passed on to company shareholders, and some would likely be used to lobby to keep the yield above MVI forever.

From a macro perspective, the benefits of MVI

I have often thought that the penetration of Ethereum into the ecosystem is desirable. In the case of L2, bridging Ethereum will bind L1 and L2 together and provide external funds to users on L2, thereby increasing their financial security.

If you create a system where users have to rely on some opinionated ETH derivative as funding to avoid inflation taxes, then the entire ecosystem is more vulnerable to disruption.

For example, consider the following scenario: users who cannot stake provide their ETH to an organization (SSP) that runs a validator for them. These organizations can issue LST as collateral and use it on Ethereum.

If the protocol does not operate under MVI, but operates with a higher deposit ratio, one or a few LSTs may replace the currency in the Ethereum ecosystem, embedding it into every layer and application. What impact will this have?

First, the positive network externalities arising from the currency function may allow an LST to maintain its dominance while its SSPs provide a poorer service than their competitors (e.g., charging higher fees or offering only poorer risk-adjusted rewards).

Secondly, and most importantly, LST holders and any applications or users that need LST to maintain its value will share a common fate with LST and the eventual LST issuing organization (SSP).

This would require Ethereum to destroy a large part of itself. Affected users may be more willing to reinterpret errors or misconduct as something completely different. Once you become the currency of Ethereum, you become the social layer in a way. We no longer only care about the proportion of staked ETH under LST, but the proportion of total ETH under LST. Corrupt institutions are correspondingly also located on a layer above the consensus mechanism.

It is clear from The DAO that if the proportion of total circulating supply affected by the outcome becomes large enough, the “social layer” may waver in its commitment to the underlying intended consensus process.

If the community can no longer effectively intervene in events such as a 51% activity attack, then risk mitigation in the form of the early warning systems Buterin discusses may not be effective.

In this case, the consensus mechanism became so large and interconnected through derivatives that its ultimate arbiter - the social consensus mechanism - became overloaded.

Now consider a different scenario under MVI. First, each LST will face tougher competition from non-staked ETH. Therefore, the ability to monopolize currency functions and then charge high fees or offer higher-risk products will be weakened.

Second, the social layer will continue to be natively tied to Ethereum and ETH, rather than to external organizations and their issued ETH derivatives. The collateralization ratio is kept low enough through MVI, thus changing the risk calculation for participants.

Under MVI, when the collateralization ratio is low enough to prevent moral hazard from developing, the principal-agent problem (PAP) of delegating staking to a dominant LST can be more accurately priced. No LST will grow to the point of being “too big to fail” in the eyes of Ethereum’s social layer.

This pricing will reflect the fact that the larger the share of stake controlled by an agent acting on behalf of the principal (or any party that can intervene in the relationship), the better its chances of degrading consensus for its own benefit.

A delegating staker must always consider what security guarantees it has (e.g., the staker’s or the intervening party’s own value at risk), knowing that if the worst happens, it could lose everything.

Removing the direct dominance of Ethereum currency, and assuming that the deposit ratio has grown to a utility-maximizing size under MVI, larger SSPs are likely to find non-monopolistic strategies more profitable (i.e., increasing fees).

This is only a comment relevant for now. But importantly, it reflects the fact that for every “cartel stratum” we are able to eliminate, the value proposition of a secure and value-aligned SSP increases in relative terms.

An important step towards MVI is MEV burning, which also has the potential to eliminate the "cartel class" that is more important than the currency function. MEV burning helps reduce the variance of rewards for independent stakers, which would increase if the issuance yield is reduced.

It also brings greater precision to targeting MVI because it eliminates a source of revenue that can vary over time in ways that cannot be predicted in advance.

It’s worth noting that various approaches may be developed in the future to deal with the principal-agent problem for certain aspects of delegated staking (i.e. one-time signatures). But the fundamental issues of trust building, monopoly incentives, and censorship resistance may be difficult to escape.

Another benefit of MVI is that it improves the conditions for (independent) staking, which is related to the direct relationship between stake size, number of validators, and validator scale. If the stake size changes, the validator scale or number of validators (network load) will also change.

This effect spreads across the entire protocol design space and affects any targets that could be replaced to achieve higher or lower network load, such as parameters related to variable validator balances.

This is a fundamental property of the current consensus mechanism. If the issuance policy resulted in d= 0.6 at the mid-term equilibrium point instead of d= 0.2 , then independent staking would require three times as much ETH to maintain the same network load, ceteris paribus.

Going back to the basics, I think the most important benefit of MVI is its ability to provide utility to the average user. Ethereum is in a unique position to enable the native cryptocurrency to become a global currency, and I think this is an opportunity worth pursuing.

When states impose price inflation by increasing the monetary base, they control the temporal choices of ordinary people and believe that such control is still feasible in a digital and globalized world.

Ethereum shouldn’t control ordinary people, nor force them to save liquidity energy. We should allow them to maximize the convenience of using Ethereum currency and gain utility from it. The “risk-free rate” in Ethereum is simply holding (and trading) ETH.

Solving potential problems with MVI

After laying out the potential benefits of MVI, the second section will address some of the proposed drawbacks. These include reduced economic security and the notion that delegated staking will replace all independent staking if we reduce yields.

When it comes to the first point, this is indeed true, as a higher deposit ratio does force an attacker to expend more resources, e.g., to restore finality. This is not something to be taken lightly.

Our goal is not “minimum issuance”. We must always ensure it is “feasible”. Buterin provides some intuitive explanations for how expensive a 51% attack on Ethereum should be.

We can also think of the nearly 14M ETH securing Ethereum at the time of the merge as the “preference” of the stake size that the ecosystem deems secure enough under the current consensus mechanism (in terms of resistance to Lady Ledger attacks, not just super committee accountability).

At the same time, it’s nice to have a decent margin, and the current collateralization ratio (d 0.2) relative to the collateralization ratio at the time of the merger (d 0.1) may also provide a meaningful improvement in terms of resistance to fake accounts.

The slope of the reward curve cannot be too steep, which is why we may want to operate at some distance from the preferred point, and ultimately d can be determined from a probabilistic analysis of stake supply and demand.

Some may argue that delegating stake somehow makes it easy to attack resource allocation, and that it is only “superficially” secure. But by making all stakers subject to penalties and removing moral hazard (via MVI), delegators must be very careful when delegating stake, as discussed above.

In this setup, the market determines the appropriate capitalization rate for staking operators and prices the risk of staking. Instead, Ethereum is responsible for punishing misbehavior and maintaining the value of ETH relative to the value it secures.

By ensuring that ETH tokens permeate the real economy and that all consensus participants have a real stake, we set a price for attacks that is much harder to circumvent through financial engineering.

I mention this because there are indeed some interesting alternatives being discussed where Ethereum intervenes in the delegation process and there is no risk to the delegators. Then the risk to the delegators contributing to consensus deterioration would be much lower.

Or at least that’s how it seems. If the worst happens when Ethereum forks and/or must be rescued by social intervention, risk-free delegators may be surprised by how the social layer values their delegation and the damage they are perceived to have caused.

Here I return to Buterin’s plea not to overload consensus. My point and a theme of this article is that when a very high percentage of ETH is involved in the consensus process, everyone is involved and a “neutral” outcome may not be possible.

The conclusion to the first question is that d under MVI must be kept large enough to ensure safety, and delegation does reduce safety to some extent, but as long as their pledge is risky, parties will try to assess the risk and delegate wisely.

Retaining independent stakers is indeed a complex puzzle. Economies of scale are hard to engineer away, and we haven’t paid enough attention to liquidity in staking. However, there are some nuances in the current argument that favor MVI that I hope to bring up.

Ethereum’s solo household stakers incur certain costs when they stake. They pay a large portion of their fees upfront, including knowledge acquisition. They also incur variable costs such as bandwidth, troubleshooting time, and outage risk.

Many of Ethereum’s SSPs also incur significant costs in designing their services and bear other types of operational costs that independent stakers don’t have to worry about. However, they rely on economies of scale to reduce the average cost of operating a validator.

We must assume that the SSP seeks to maximize profits and can consider what their costs might be at different equilibria. How do the economies of scale differ between d= 0.2 and d= 0.6? It seems reasonable to assume that the SSP has much lower average costs at d= 0.6.

Remember that at d= 0.2 , a solo staker might be able to run a validator that is three times smaller than at d= 0.6 . In terms of the fraction of solo stakers we can attract, there could be a difference between a minimum validator of 32 ETH and 96 ETH (or 11 ETH - 32 ETH).

So not only will a higher d force independent stakers to stake more ETH for the same network load, they will also have to compete with SSPs who can charge lower fees. While fees will be set based on market strategy, average cost should ultimately matter.

If we reduce yields, SSPs will hopefully need to raise fees to properly cover and amortize costs. Costs to delegates are variable, including PAP and fees. They can easily get away with increased fees.

The argument that lowering returns will cause independent stakers to leave (before delegated stakers) should be taken seriously, but since current family stakers have already incurred fixed costs, their current personal return supply elasticity may not be high.

However, their lower resilience in the short term will not help if we reduce the returns to a point where independent staking by households becomes unfeasible (including for new entrants). If we want to maintain independent staking, there is a floor on the total return on staking that we cannot go below.

Assume that the total cost of staking for an independent household (in ETH) is C, and consider other factors such as the annual risk to funds when staking R. Then, the return must be higher than y>C/32+R, and even if re-staking brings liquidity, a reasonable margin is required.

Here, I also want to discuss the impact of DeFi income. All stakers will receive income y that is endogenous to staking. This "endogenous income" comes from issuance, MEV, and priority fees. Some people may also receive "exogenous income" yc outside the consensus mechanism.

It is not possible to simply sum y+yc for LST holders and conclude that no matter how y decreases, LST holders always gain relative to independent stakers. It is expected that ETH tokens will have higher utility relative to LST (without considering its intrinsic benefits).

Delegated stakers must weigh y(1-f), where f is the percentage fee, against the risks/costs including the inherent disadvantages of PAP and LST relative to native ETH, and decide to stake only when y(1-f) (not y+yc) exceeds these costs.

When y= 0, agents will not delegate staking. They can get better liquidity or higher yc through native ETH, and face severe disadvantage by delegating staking to an SSP that operates at a loss. Independent stakers may also not stake.

For someone who wants to hold ETH anyway, the decision may not depend on whether yc is 1% or 5%. At 5%, ETH can be expected to provide +5%. Of course, that 5% comes with risk and is not free money (nor should our returns be, hence MVI).

As y rises, potential independent and delegated stakers will gradually find the proposition of staking worthwhile, starting with the most ambitious/risk-taking. Here we are forming a supply schedule where each agent makes decisions based on their specific circumstances.

It is unclear what the minimum expected yield distribution is between potential independent stakers and delegated stakers. At the medium-term equilibrium point of d= 0.2, the proportion of independent stakers may be lower than d= 0.6, but the other option is also likely.

A higher d might allow for greater diversity in SSPs, but the monetary cartel puts pressure on this. There is also a limited fraction of individuals who have enough ETH to stake independently, which sets a soft cap on the total number of independent stakers.

This is indeed a topic worthy of further research. The key point is that the opportunity cost of staking must always be fully considered, and economies of scale and monopoly can affect the basic equilibrium analysis in quite complex ways.

Finally, re-staking has the potential to make independent stakers more competitive. It enables them to “re-stake” their stake when they wish (however, they themselves may also run into principal-agent problems if they want to provide economic security).

One benefit of restaking is that if Active Validation Services (AVS) can quantify decentralization, it can also assign economic surplus value to decentralization. This is something that Ethereum as an open protocol cannot do.

The previous argument also applies to re-staking on out-of-code EigenLayer functions. At very low yields, users are better off just using unstaked ETH (free staking). For many use cases, it seems reasonable that AVS would prefer a token that doesn’t evaporate easily.

Note also that if PEPC expands its scope beyond the “block production use case”, the benefits generated may become more endogenous, depending on the residual utility provided.

Looking ahead

This concludes our discussion of the pros and cons of MVI. While there are some concerns about solo staking, MVI is a fundamentally sound design policy that gives Ethereum a real chance to provide users with the best digital currency ever created.

Each argument has its nuances, and some discussions cannot be succinctly expressed in a tweet. But I think all things considered, it should be possible to accept that MVI is also a favorable design principle under PoS.

We must always focus on the “average user” first, which requires research at the micro-foundations level and evaluating how we can maximize utility for the average person as Ethereum (hopefully) becomes their new financial system.

The question then is how do we achieve MVI, which is something I’ve been diving into. Dietrichs mentioned the importance of communicating current release policy research on a recent developer call, and my process started with this tweet.

Changing the issuance policy is a sensitive issue. What we desire is an issuance policy that maximizes utility and requires no further developer intervention, so that it always allocates MVI proportionally to maximize utility.

However, the current reward curve does not allow the protocol to influence the collateralization ratio (security), but rather the collateralization size. In the medium term, the results are closely related to these two, but in the long term equilibrium, there may be a clear divergence as the circulating supply drifts.

This is the topic of my 2021 Ethresearch article and Devconnect talk: Defining how the circulating supply S drifts towards equilibrium (i=b) so that we can improve the rewards curve and achieve minimum viable issuance under proof of stake.

Since the issuance amount i can be expressed as i=cFd/S according to the current reward curve, it will change with the change of circulating supply (the mortgage rate d provides some adjustment space). The figure shows the diagonal of Ethereum's issuance rate and the average b since the merger.

The burn rate b does not depend on the circulating supply - the demand for block space does not change due to changes in the currency unit of account. If i>b, S will rise and pull i down until it equals b. If i

In 2021, stakers do not have REV yet, so I directly used the minimum expected rate of return y-, and concluded that the security of Ethereum is d=b/y.

Today, we simply add the “REV rate” v to the equation and get d = (b + v) / y. This means that we cannot control the collateralization rate and security in the long run unless we are prepared to change F from time to time.

We can slash F as a temporary solution to avoid paying excessive security fees (this will be discussed in the next tweet). However, Ethereum will eventually return to the same long-term equilibrium collateralization ratio at a lower circulating supply (other things being equal).

This is why we eventually want to change the reward curve to be tied to d instead of D. It would then seem tempting to simply replace D with S 0 d (where S 0 is the current circulating supply). This brings us one step closer to a self-governing issuance policy, but there is still no guarantee that we will achieve it.

Assuming MEV burning, the protocol is fully adaptable to changes in revenue, but still cannot adapt to permanent shifts in expected yields, i.e. the supply curve. This can be handled by allowing the entire reward curve (demand curve) to drift slowly.

The ultimate goal is a dynamic equilibrium where the circulating supply can change at a constant rate without external influences. Whether it is inflationary or deflationary depends on the supply curve and how the value of block space is reflected in the ETH market cap.

We thus achieve what Polynya calls “constant” security, which I think aptly describes our ultimate goal of ultimately taking control of issuance away from developers and making Ethereum autonomous under MVI.