The first time you truly understand why “storage” is a serious crypto problem, it usually isn’t from a chart or a token thread. It’s when something breaks. A dApp’s frontend disappears because it was hosted on a normal server. NFT metadata returns 404. A research team loses access to a dataset because a cloud account got frozen or the bill didn’t get paid on time. Markets love to price blockspace, but most applications don’t fail because transactions are expensive. They fail because the data layer is fragile.

Walrus exists because of that gap. It’s not trying to be another general-purpose blockchain. It’s trying to be the storage system that actually behaves like infrastructure: cheap enough to use at scale, resilient under stress, and verifiable in a way that doesn’t require blind trust. Walrus Mainnet is live and runs as a production network on Sui, operated by a decentralized set of storage nodes, with committees chosen through staking and epoch based operation.

For traders and investors, the easiest mistake is treating Walrus like a “DeFi protocol with a storage narrative.” That framing misses what you’re really looking at. Walrus is architecture. It’s the plumbing for data heavy apps that can’t realistically put everything directly on chain AI agent memory, media files, game assets, social content, research archives, and the boring but important stuff like documents and regulatory records. Walrus is purpose built for large binary objects, what it calls “blobs.”

At a high level, Walrus splits into two layers: a control plane and a data plane. The control plane lives on Sui. That’s where coordination happens: storage purchases, committee selection, accounting, and on chain objects that represent storage commitments. Sui provides the programmability and settlement logic, while Walrus focuses on storing and serving actual data efficiently. This is a key design decision because it avoids reinventing a full blockchain just to manage storage node coordination.

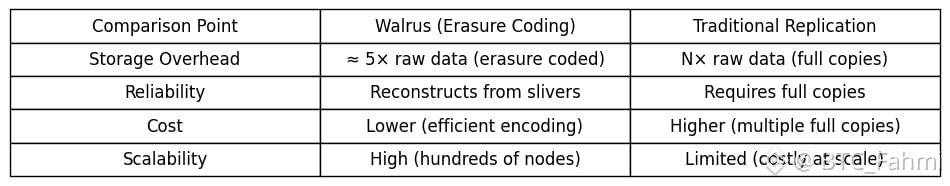

The data plane is where the interesting engineering lives. Walrus doesn’t store full copies of files across nodes (full replication), because replication gets expensive fast. Instead, it uses erasure coding a blob is encoded into many smaller redundant pieces called “slivers,” and these slivers are distributed across a committee of storage nodes. So the network can lose some pieces and still reconstruct the original blob. Walrus’ documentation describes this as a cost efficient approach where the storage overhead is roughly about 5× the raw data size, trading some redundancy for reliability without the extreme cost of copying everything everywhere.

Walrus takes erasure coding further with a specific encoding protocol called Red Stuff. In the academic write up, Red Stuff is described as a 2D encoding method that is “self-healing,” meaning the system can recover lost slivers efficiently, with bandwidth proportional to what was lost, rather than requiring a full re-encoding event. That matters because in real networks, nodes go offline constantly: hardware dies, providers fail, operators disappear, and sometimes people are just sloppy. If a storage network can’t heal itself cheaply, it slowly decays.

Now zoom in to how participation actually works, because that’s what investors tend to care about after the thesis: who does what, and what incentives keep them honest.

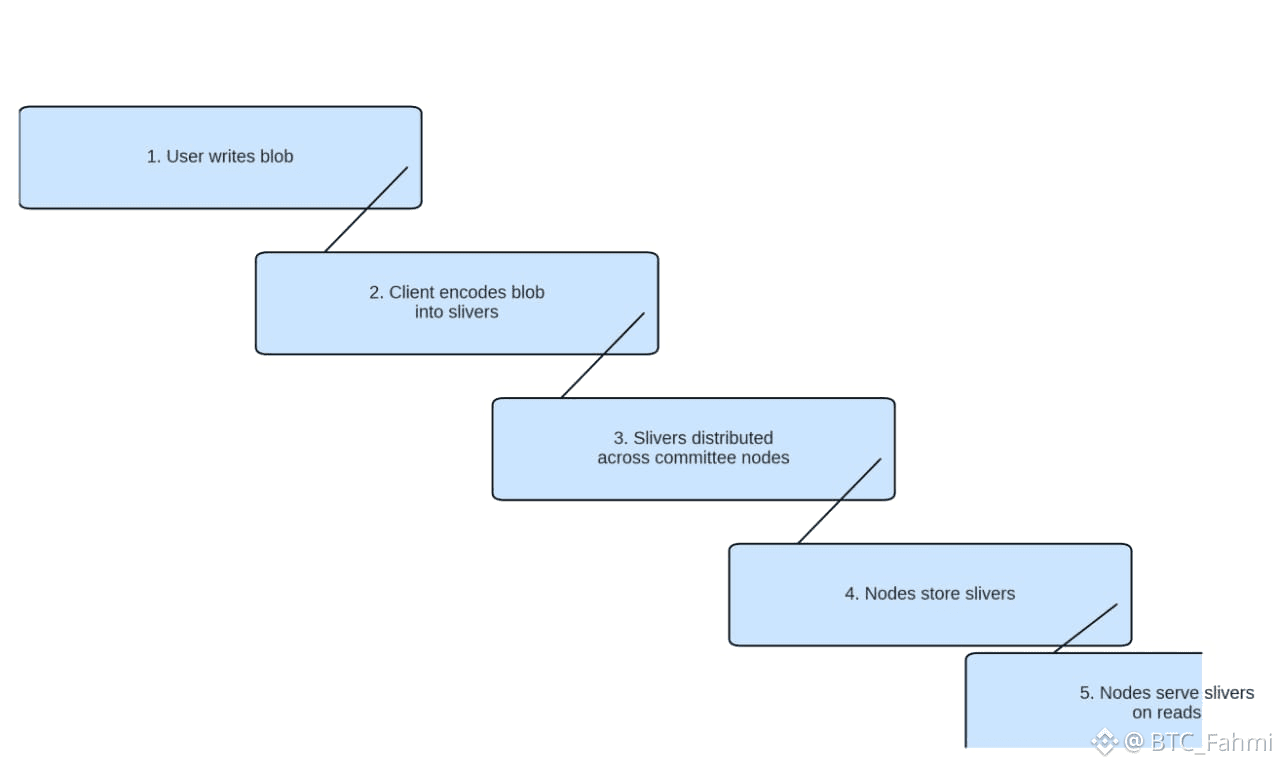

Walrus runs in epochs. Committees are selected for an epoch, and each committee is responsible for storing slivers for blobs. Storage nodes hold slivers from many blobs, not entire blobs. When a user writes a blob, the client coordinates with the active committee to encode the blob into slivers and distribute them. The blog describing how blob storage works emphasizes that the client orchestrates writing, while nodes store the slivers and later serve them on reads.

Staking is central. Nodes stake WAL to participate and to influence committee selection. WAL isn’t just “gas” for storage. It’s the governance and security lever: nodes and delegators stake it, committees are formed based on stake, and governance adjusts parameters like penalties and economic settings. If you’ve spent time watching validator economics on L1s, the logic will feel familiar: rewards to maintain service, slashing or penalties to punish underperformance, and voting power tied to stake.

What I find genuinely distinctive here, from a market perspective, is that Walrus is not competing on ideology. It’s competing on operational practicality. A huge amount of Web3 “decentralization theater” still depends on centralized storage for everything that isn’t a simple state transition. Walrus explicitly targets that reality: large-scale blob data that needs to be available, retrievable, and defensible against censorship or platform risk.

Here’s a grounded example that traders can relate to. Imagine a research analyst building a dataset-driven strategy product: dashboards, time-series archives, and AI-generated reports. If the core dataset is hosted on a normal cloud bucket, a single billing issue, policy violation, or regional outage can break the product overnight. The chain can still settle transactions, but the product becomes unusable. With Walrus, that same dataset can be written as blobs with verifiable storage commitments, so the availability risk moves from a single vendor to a distributed committee with staking incentives and penalties. It doesn’t eliminate risk, but it transforms it into something closer to infrastructure risk rather than platform risk.

So if you’re evaluating Walrus as an investor, the more honest question is not “will storage be a narrative?” Storage always becomes a narrative in bull markets. The sharper question is whether Walrus’ architecture can become a default backend for data-heavy on-chain apps because it solves three hard problems at once: cost, reliability, and coordination. Walrus claims scalability to hundreds of storage nodes with high resilience and relatively low overhead via erasure coding.

If that design holds up under real usage, Walrus stops being “a protocol.” It becomes boring infrastructure. And in markets, boring infrastructure is often where the most durable value quietly accumulates.