@Walrus 🦭/acc Most people only notice storage when it fails. Not in an abstract way, but in the way your stomach tightens when a link breaks, a file won’t load, or a product suddenly feels like it was built on sand. Walrus exists inside that emotional gap. It is trying to make “large blobs” feel boring again—media, models, archives, datasets, the heavy objects that don’t fit neatly on a chain but still need to be treated like first-class truth. When Walrus works, nobody claps. Things simply keep showing up when they’re supposed to.

The deeper reason Walrus matters is that big data is where trust gets expensive. A tiny on-chain message can be verified by a lot of machines without much drama. A large blob is different. It is slow to move, costly to replicate, and easy to mishandle without anyone noticing until the worst moment. When you build with Walrus, you aren’t just choosing where data sits. You’re choosing what kind of failure you can live with. You’re choosing whether your users will experience your app as dependable during pressure, or as one more system that quietly disappears when conditions get noisy.

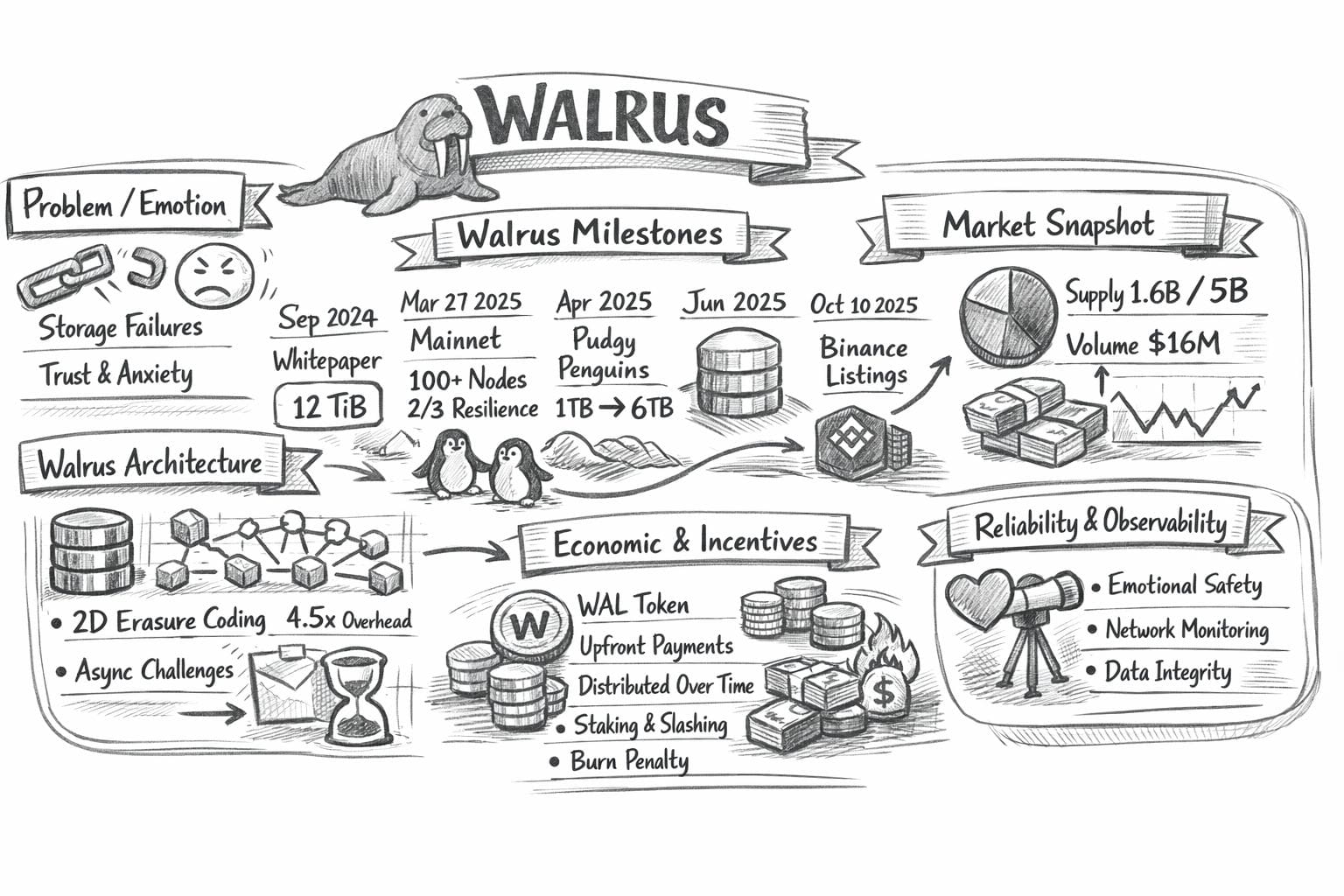

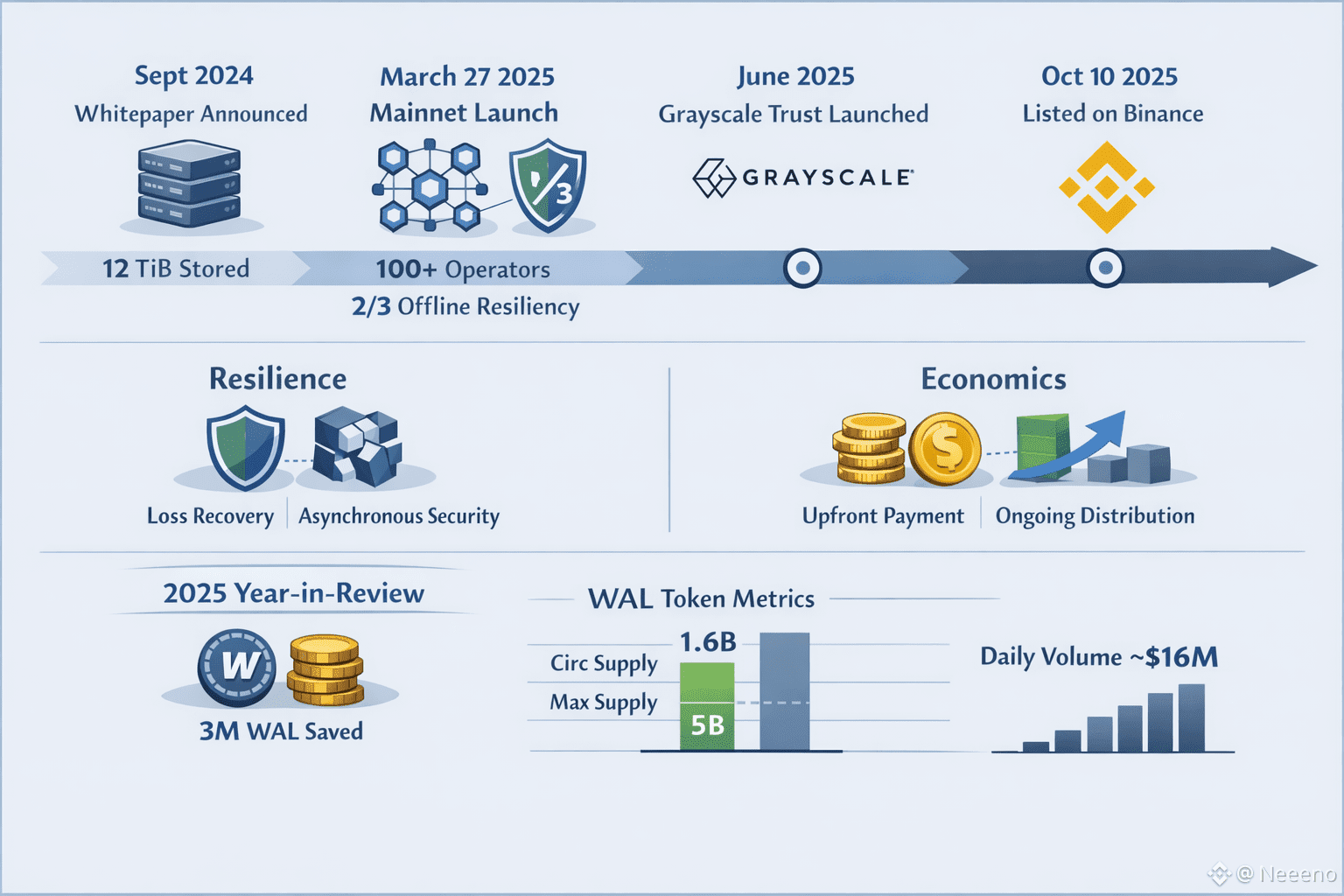

Walrus came into public view in stages that reveal how seriously it takes that risk. First there was the developer preview, with Mysten Labs noting that it was already storing over 12 TiB of data at the time the official whitepaper was announced in September 2024. That detail matters because “storage” is easy to describe and hard to carry. Storing terabytes is not a marketing claim; it is a living promise that has to survive churn, misconfiguration, and the kinds of mundane operator errors that never make headlines but ruin real products.

By March 27, 2025, Walrus went to mainnet, and the language around it shifted from experiment to responsibility. The mainnet launch post points to over 100 independent node operators and makes a concrete resilience claim: even if up to two-thirds of nodes go offline, user data should still be available. You can read that as bravado, but if you’ve ever maintained anything at scale, you read it as a design philosophy: assume bad days are normal, and build so the system doesn’t panic when reality gets messy.

Under the hood, Walrus is not built around the romantic idea that everyone stores everything. It is built around a more pragmatic question: how do you make loss survivable without paying the full cost of paranoia? The Walrus research paper describes a two-dimensional erasure coding approach that aims for strong security with roughly 4.5× overhead while enabling recovery that pulls bandwidth proportional to what was lost, rather than re-downloading the entire blob. This isn’t a small technical preference. It shapes how users experience the network during stress. Recovery that is surgical feels like competence. Recovery that is blunt feels like fragility.

There is also a quieter threat that blob systems face: time. Not the poetic kind—network delays, asynchronous conditions, partial partitions, the long tail of weird latency that shows up precisely when you most want clean guarantees. The same paper emphasizes that Walrus’ challenge design is meant to hold up even in asynchronous networks, so a node can’t exploit delays to look honest without actually holding data. That’s the kind of sentence that sounds academic until you translate it into human consequence: it’s the difference between a storage promise that can be gamed when the internet gets ugly, and a storage promise that stays meaningful when the internet acts like the internet

Walrus is also explicit that it wants to be a data availability layer for large blobs, not just a place to park files and hope. That’s why it leans on verifiability as a felt experience, not a theoretical property. People don’t trust storage because a team says “it’s decentralized.” They trust storage because, week after week, the blob that matters can be retrieved, checked, and served without begging a centralized gatekeeper to be in a good mood. Reliability becomes a form of emotional safety: the sense that your product won’t embarrass you in front of users when traffic spikes or a partner integration goes sideways.

You can see this philosophy show up in the ecosystem stories Walrus highlights, where the “blob problem” stops being a concept and turns into operational pressure. In April 2025, Pudgy Penguins announced an integration with Walrus to store and manage a growing media library, starting with 1 TB and planning to scale to 6 TB over the next 12 months. That isn’t just about cute images. It’s about brand continuity. It’s about not waking up one day to discover your digital identity is scattered across accounts, teams, and tools that don’t agree with each other. Walrus is being asked to hold the parts of a product that people emotionally attach to, which raises the bar in a way a developer demo never can

Walrus also keeps circling back to a specific economic truth: storage is not “free,” and pretending it is creates incentives that collapse at the first sign of strain. WAL is positioned as the payment and incentive token designed to keep storage costs stable in fiat terms, with payments made upfront for a fixed period and then distributed over time to the parties doing the work. That time-distribution detail is important. It acknowledges that storage is a continuing service, not a one-time event, and it tries to align compensation with the reality that data must remain available tomorrow, not just today

The WAL design also tries to confront an uncomfortable part of decentralized infrastructure: people behave well until it stops paying. Walrus frames staking and delegation as a way to route responsibility toward operators who actually perform, and it openly states that low performance can be punished through slashing, with a portion burned. This is where “tokenomics” stops being a trader’s spreadsheet and becomes a governance of trust. When you stake or delegate, you’re not just chasing yield—you’re choosing who you believe will show up consistently, and you’re accepting that the system will penalize wishful thinking

By late 2025, the WAL story moved from internal mechanics to broader market accessibility. A Chainwire piece republished by Investing.com notes that WAL was listed on Binance Alpha and Binance Spot on October 10, 2025, framing it as another milestone after the March 2025 mainnet launch and referencing a $140 million private token sale. Listings don’t make infrastructure true, but they change the social environment around a network. More liquidity can mean more participation, more scrutiny, and more volatility. For builders, that volatility is not entertainment—it’s a risk factor. The system has to keep behaving while the token mood swings.

That’s why the most convincing Walrus updates aren’t the flashy ones; they’re the ones that reduce operational friction without weakening guarantees. In its 2025 year-in-review, Walrus claims that improvements aimed at efficiency saved ecosystem partners more than 3 million WAL, which is the kind of number you only bother tracking when costs are real and usage is non-trivial. Savings like that are not just about expense; they change which kinds of products become viable. They let smaller teams ship without building a pile of off-chain patchwork just to make uploads tolerable.

The same year-in-review also describes growing institutional attention, including a statement that Grayscale launched a Walrus trust in June 2025. You can interpret that as validation if you want, but the more practical takeaway is that Walrus is being pulled into environments where “availability” means contractual obligations and reputational risk, not just user complaints on social media. Institutional interest has a way of turning soft promises into hard expectation

Around August 2025, a Chainwire release about a partnership between Space and Time and Walrus framed something equally unglamorous but essential: visibility into network health, activity, reliability, and performance through a dedicated explorer and analytics layer. Observability is one of those things nobody asks for until a crisis starts, and then it becomes the only thing that matters. When a blob goes missing or a service slows down, you don’t want inspirational narratives—you want concrete telemetry. You want to know which operators are behaving, what availability checks show, and whether the system is healing or silently degrading.

Even the market snapshot around WAL tells a story about what Walrus is trying to stabilize against. CoinGecko’s page (as of the capture shown) reports a circulating supply of about 1.6 billion WAL out of a maximum 5 billion, with market cap and FDV estimates derived from that supply, along with a 24-hour trading volume just under $16 million. None of those numbers are eternal, but they illustrate the environment Walrus has to survive: a token that trades continuously, sentiment that changes daily, and a network that still has to store and serve blobs with the same calm consistency regardless of the chart.

This is the part that people underestimate: Walrus is not just fighting technical failure, it is fighting narrative failure. In a volatile market, every slowdown gets interpreted as doom, and every recovery gets interpreted as luck. A blob system can’t afford that emotional rollercoaster. It has to make correctness feel routine. It has to make “I can retrieve my data” feel like gravity, not like a special event. The protocol’s research emphasis on efficient recovery under churn and strong guarantees under asynchronous conditions is, in a sense, an attempt to remove drama from the user experience.

And churn is not hypothetical. Operators change machines. ISPs fail. Regions go dark. People chase better margins. Sometimes teams simply disappear. Walrus’ own writing about decentralization at scale focuses on resisting the natural pull toward concentration by tying rewards to verifiable performance and penalizing poor behavior and rapid stake shifts. You don’t have to agree with every framing to see the intent: keep the network from becoming a small club, because blob storage controlled by a small club is just centralized storage with extra steps.

If you build on Walrus, you eventually stop thinking about “storage” and start thinking about responsibility. You start thinking about what it means to tell users, “your data is here,” and to be able to say it without crossing your fingers. You start noticing how many systems in crypto treat data as a temporary side effect—something you can pin, cache, or reconstruct—until one day you can’t. Walrus is trying to be the layer that doesn’t blink when everyone else is improvising.

The most honest way to judge Walrus is to imagine the moments nobody wants to imagine: a sudden wave of demand, a coordinated attempt to cheat, a noisy network day where latency lies to you, a slow bleed of operator reliability, a token price that whiplashes and makes incentives wobble, an application that becomes culturally important and therefore politically tempting to censor. Walrus is not promising a world without those moments. It is trying to engineer a world where those moments don’t automatically turn into catastrophe, where recovery is built-in, where incentives are shaped around long-term behavior, and where the economics of WAL are designed to keep the service legible to humans who budget in real currency.

In the end, Walrus is a bet on quiet responsibility. It is a bet that the future will be shaped less by loud claims and more by invisible infrastructure that keeps its word. Mainnet in March 2025 was not the finish line; it was the point where promises became load-bearing. The partnerships, the terabytes stored, the operator set, the WAL mechanics, the supply reality, the exchange listings, the observability work—these are all different angles on the same question: can Walrus stay dependable when nobody is watching, and when everybody is watching for a mistake

That’s why reliability matters more than attention. Attention is a season. Reliability is a duty. Walrus, at its best, is the kind of system you don’t think about until the moment you need it—and then it’s simply there, holding the heavy things, absorbing the chaos, and refusing to turn your users’ data into a hostage of mood, markets, or mistakes.

Článek

Walrus: A Storage and Data Availability Layer for Large Blobs

Vyloučení odpovědnosti: Obsahuje názory třetích stran. Nejedná se o finanční poradenství. Může obsahovat sponzorovaný obsah. Viz obchodní podmínky.

WAL

--

--

BTC

67,989.18

-0.68%

0

5

844

Prohlédněte si nejnovější zprávy o kryptoměnách

⚡️ Zúčastněte se aktuálních diskuzí o kryptoměnách

💬 Komunikujte se svými oblíbenými tvůrci

👍 Užívejte si obsah, který vás zajímá

E-mail / telefonní číslo