@Walrus 🦭/acc For most game teams, “data” isn’t a buzzword. It’s the live layer that keeps a world coherent: textures, audio, patch bundles, anti-cheat rule files, player replays, marketplace images, community skins, and the tiny configuration flips that quietly stop yesterday’s bug. For years we treated that as plumbing, rented from a cloud bucket and a CDN, invisible until something leaked. Now the plumbing shapes the game itself. Players expect persistence, creators expect their work to outlast a season, and publishers increasingly want audit trails they can defend when something gets disputed. That change is emotional as much as technical. Nobody wants to tell a community that a decade of creations is gone because a link rotted.

Walrus keeps coming up in that shift because it aims at the part most chains sidestep: big files. Walrus is a decentralized storage and data-availability protocol built for large “blobs,” with the Sui blockchain acting as its control plane for coordination, blob lifecycle, and incentives. The bytes live across storage nodes; the chain anchors references and rules. That separation matters in games because it avoids the magical thinking that you can store gigabytes “on-chain” without tradeoffs, while still giving you a public, checkable way to point to the exact thing you meant.

It feels current because it didn’t just stay an idea—it became something public and real on a timeline people can point to. Walrus put out a formal whitepaper in 2024, then launched public mainnet on March 27, 2025.

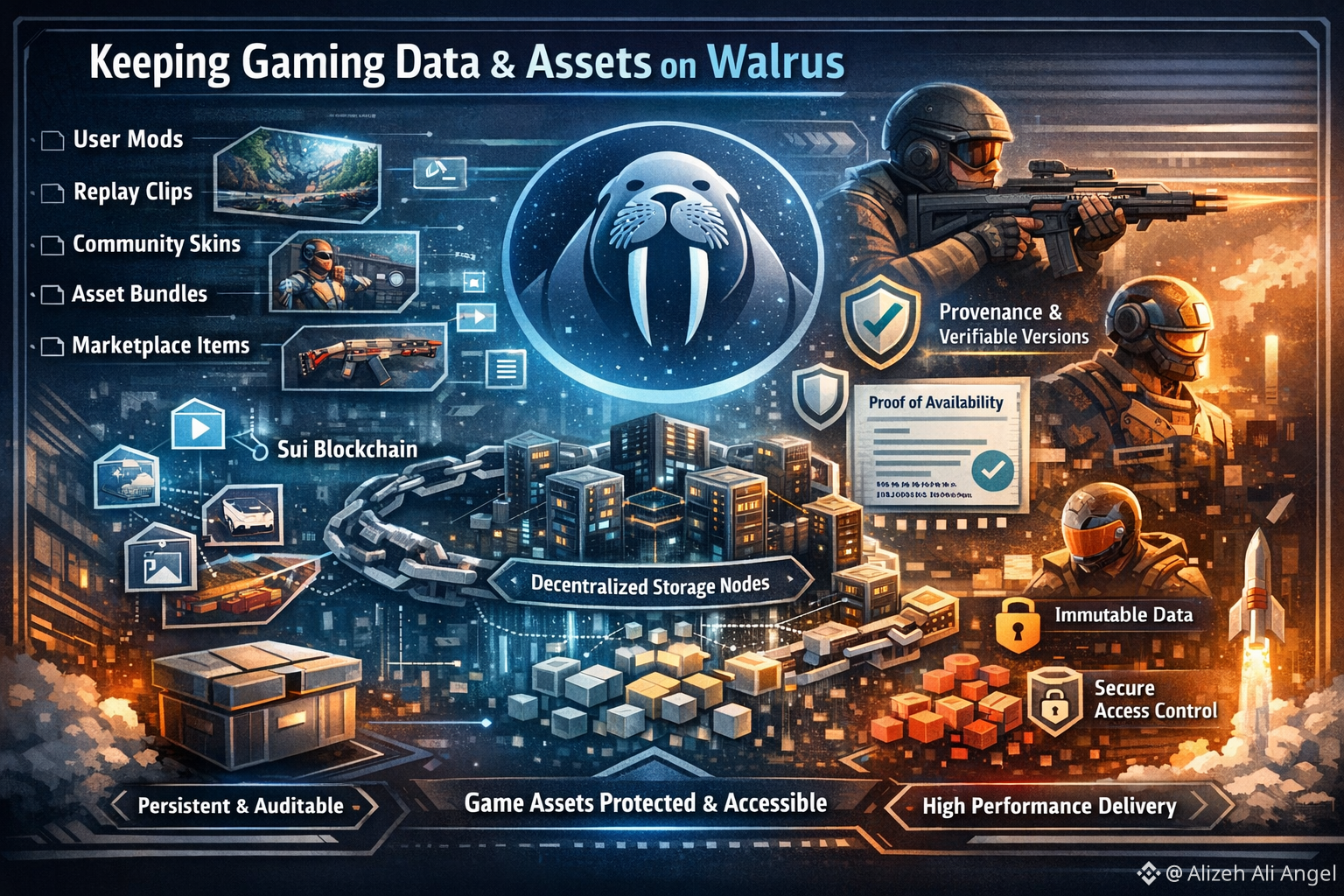

In practice, keeping gaming assets on Walrus usually means being picky. The first candidates are the files that cause the most chaos when they disappear or get quietly replaced: user-generated maps, mod bundles, cosmetic art, replay clips, and the media behind player-to-player listings. Those assets trigger hard questions. Who owns the bytes? Who can remove them? When a studio bans an item, should the data be erased everywhere, or should the game simply stop honoring the reference? A content-addressed approach nudges you toward clearer answers because the identity of the file is tied to its contents, not its location. If multiple users upload identical content, Walrus can reuse the existing blob rather than creating duplicates. That’s a small detail with big implications for games built on remixing and reposting.

There’s also a calm, unglamorous win that tends to matter most during a bad week: versioning you can defend. Live games suffer from the “which file did you mean?” problem. A balance table changes, a texture is rebuilt, a ruleset is hot fixed, and suddenly half the player base is looking at a different reality. With immutable identifiers, it becomes harder to accidentally point at a moving target, and easier to reproduce a bug with the exact assets a player had at the time. Walrus leans into this with on-chain lifecycle management and proof mechanisms—its docs and technical posts describe generating proof-of-availability certificates tied to stored blobs. When disputes show up (duplicate items, contested trades, “this replay was tampered with”), being able to say “this is the exact file we referenced” is not a philosophical flex; it’s a support ticket closer.

Performance is where the romance ends and the engineering starts. Players don’t forgive slow downloads, and studios shouldn’t gamble a launch on a fragile network path. Walrus’s design leans on erasure coding—described in the whitepaper as “Red Stuff”—to get resilience without simply storing full copies everywhere. In plain terms, data is split into coded fragments distributed across many nodes so it can be reconstructed even if some nodes fail or churn. The academic write-up argues this approach can balance recovery efficiency, security guarantees, and storage overhead in ways older designs struggle with. Still, the most realistic game architecture is hybrid: keep latency-critical delivery on conventional caching paths, and use Walrus where durability, integrity, and “this reference should still work later” are the primary requirements.

A newer, surprisingly game-relevant angle is privacy and access control. Walrus has been framed as a public data layer, and Mysten Labs has shipped Seal, an encryption and access-control system designed to work alongside Walrus so data stays encrypted until a policy allows decryption. In game terms, that opens doors for gated cosmetic drops, private tournament builds, protected creator-tool exports, or sensitive replay and telemetry artifacts shared with trusted parties without turning them into public downloads. It also shifts the mental model: instead of relying solely on “who can hit this URL,” you start thinking in terms of “who can unlock this data,” which is closer to how modern games already try to reason about entitlement.

The most compelling part of Walrus, to me, is the discipline it forces. Not every file deserves forever, and not every community artifact should depend on one vendor’s retention policy. Walrus won’t solve your design problems, and it won’t magically make moderation easy. But it can make promises about persistence, provenance, and verifiable versions less brittle, especially for the parts of games that are becoming more like culture than content drops. If you’re serious about trying it, start small: pick one asset class you can isolate, measure retrieval behavior under real load, and learn what your players actually want you to keep.