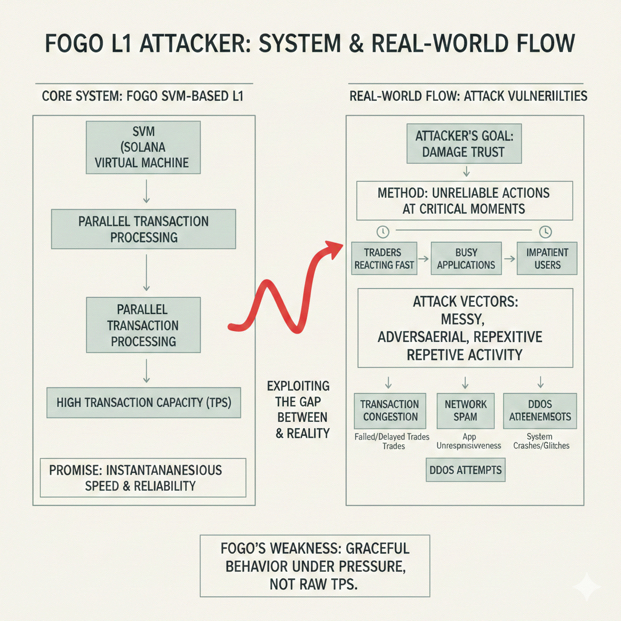

Fogo as an attacker instead of a fan, the first thing I notice is that its entire promise is built around the experience of speed, and that means the easiest way to damage trust is not by trying to “kill the chain,” but by making normal actions feel unreliable at the exact moments people care most, such as when traders are reacting fast, when apps are busy, and when users are already impatient because they were told everything should be instant. Because Fogo is an SVM-based L1, the real story is not only how many transactions it can process in a vacuum, but how gracefully it behaves when activity becomes messy, adversarial, and repetitive in the ways real networks suffer under pressure.

If I wanted to create that kind of pressure today, I would choose a congestion-style attack because it is the most practical tool for an adversary who wants maximum impact without needing a clever vulnerability, and I would focus less on raw volume for its own sake and more on where the volume lands, how it interacts with state, and how it travels through the same paths that honest users depend on. The attacker’s advantage in congestion attacks is that users rarely experience network health directly; they experience a chain through the moment-to-moment behavior of sending a transaction, seeing it confirm, watching balances update, and having applications respond without stalling, so anything that causes delays, inconsistent confirmations, or repeated failures will look and feel like downtime even if blocks are still being produced underneath.

The simplest version of the attack is straightforward: submit a large stream of transactions that are cheap to generate and easy to repeat, while intentionally shaping them to collide with the parts of the system that do not scale linearly under stress. On an SVM chain, parallelism is powerful when activity is spread across many independent accounts, but it becomes fragile when many transactions contend for the same writable state, because account access patterns force serialization where the runtime cannot safely execute conflicting writes at the same time. That is why the attacker does not need to outspend the entire network; the attacker needs to find the narrow points where many honest users naturally converge and then keep those points busy enough that the chain’s fastest path becomes a waiting line.

In practical terms, I would run the attack in layers that mirror the way users actually touch Fogo, because a chain can be technically live while still being functionally unavailable to most of its ecosystem. I would begin with a broad flood designed to stress transaction ingestion and basic verification, because even small slowdowns at the front of the pipeline create a backlog that users feel as “pending” or “failed to send,” and those feelings cause retries that add even more load, turning ordinary wallet behavior into accidental amplification. Once that baseline pressure is established, I would shift to transactions that repeatedly target the same high-traffic state patterns, because in an SVM environment it is often easier to reduce throughput by creating contention on a few shared accounts than it is to overwhelm total compute, and the outcome looks especially chaotic to users because the failures are not always consistent; some transactions land quickly while others stall, and that variance is exactly what breaks confidence.

From the outside, the attack would show up as a mix of symptoms that users interpret as instability rather than mere slowness, and that distinction matters because slowness can be tolerated while instability triggers fear. People would see transactions that take longer than expected, approvals that hang, swaps that fail in bursts, and occasional errors that feel random because they depend on timing, leader scheduling, and how crowded the contended state becomes. Developers would notice that their apps start behaving as if the network is flaky, not because their code changed, but because confirmation times and read reliability stop being predictable. Traders would feel it first because they operate on tight time windows, but the effect would spread quickly to everyone because the same congestion that delays writes also puts strain on the continuous stream of reads that wallets and apps rely on to show confirmations, balances, and state transitions.

The part that is easy to underestimate is the way access becomes the real uptime in a high-performance L1, because users do not care about internal consensus milestones if the normal act of interacting with the chain becomes unreliable. A congestion attacker understands this and tries to create a situation where the chain might still be progressing, yet the public-facing experience is dominated by timeouts, inconsistent responses, and stalled confirmations that make it look like nothing is happening. When that perception takes hold, it spreads faster than any technical incident, because people do not wait to verify whether blocks are being produced; they react to what their wallet tells them, what their app shows them, and what their peers complain about in real time.

Thinking about what would stop me, I would evaluate Fogo’s defenses in the same way I would evaluate any system that claims speed as a product feature, which means I would look for mechanisms that turn congestion into a pricing problem rather than a collapse, and I would look for controls that ensure one traffic pattern cannot monopolize the pipeline or starve honest users. The most important economic defense in a spam scenario is that sustained pressure should become expensive in a way that is difficult to evade, because if spam remains cheap during busy periods then the attacker can maintain the attack for long enough to shift sentiment and cause second-order damage. For a chain that aims to feel fast, there is a careful balance to maintain because the network cannot rely on “make everything expensive” as a solution; it needs a structure where scarce resources are priced under load, honest usage remains viable, and priority is meaningful enough to protect time-sensitive actions without becoming a tool that only attackers can afford to exploit.

On the protocol side, the key question is whether the network behaves gracefully when contention rises, which includes whether compute budgeting and scheduling rules prevent runaway patterns from clogging execution, and whether the system can isolate the blast radius when a few hot accounts become congested so that the rest of the network does not inherit the same degradation. In an SVM chain, this is where reality often diverges from marketing, because the runtime can be extremely fast overall while still exhibiting sharp performance cliffs when the ecosystem converges on shared writable state, so the strongest posture is not pretending contention will not happen, but treating it as a first-class condition and shaping the network’s behavior so it remains stable and predictable even when a few hotspots are under heavy load.

Infrastructure is the third pillar, and it is the one most visible to users during an attack, because the difference between a bad day and a disaster is often whether access remains dependable while the chain is under stress. In the attacker’s mind, endpoint reliability is a target because it is cheaper to overwhelm a widely used access path than it is to overwhelm the entire validator network, and because taking away reliable reads and transaction broadcasts creates instant confusion even among experienced users. The defense here is not one magical endpoint that “scales,” but a posture where redundancy, load shaping, and protective controls are designed for the reality that bursts happen, malicious traffic happens, and user behavior under uncertainty multiplies demand rather than reducing it.

Operationally, the most mature defense is the ability to detect user-facing degradation early and respond quickly with changes that reduce harm, because what breaks trust in a fast chain is not merely that congestion exists, but that it feels unbounded and unexplained. If monitoring only tracks whether blocks are being produced, the team can miss the moment when the ecosystem is already suffering, and the response becomes late and reactive; if monitoring includes transaction success rates, confirmation time distribution, and endpoint error patterns, then the team can respond as soon as the network starts behaving in ways that users interpret as instability. Speed-oriented networks need this discipline more than most, because user expectations are higher and tolerance is lower, so every minute of confusing behavior carries more reputational cost.

If I were writing this as a daily series that earns trust, I would anchor the analysis in a consistent measurable artifact, not because numbers are the point, but because consistency is what turns a security narrative into proof. The simplest honest artifact is a repeatable stress routine that measures what users actually feel, such as confirmation time percentiles, transaction success rates within fixed time windows, and endpoint error rates during controlled load, and then compares the results between a broad load pattern and a deliberate contention pattern that targets the same state repeatedly. When those measurements are published in the same format every day or every week, the community stops arguing about anecdotes and starts watching trends, which is exactly how a serious project builds confidence through transparency rather than slogans.

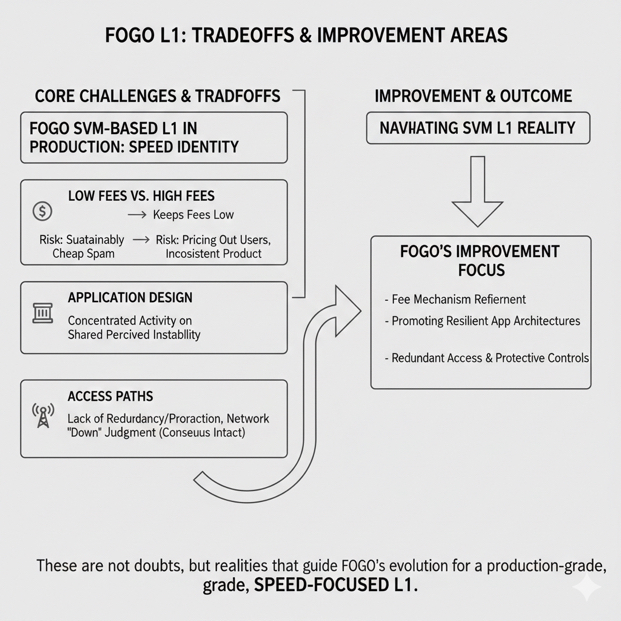

Even with strong defenses, there are tradeoffs that remain real and should be stated plainly because they guide what Fogo should improve next. If the network keeps fees extremely low during congestion, it risks making spam sustainably cheap, and if it raises costs too aggressively it risks pricing out honest users and making the product feel inconsistent. If the ecosystem builds applications that concentrate activity onto a few shared writable accounts, then the chain can face contention cliffs that look like instability even when the network is healthy overall. If access paths are not built with redundancy and protective controls, then the network can be unfairly judged as “down” during access degradation even if consensus remains intact. None of these are reasons to doubt the project; they are simply the reality of what it means to run an SVM-based L1 in production, especially one that makes speed a core part of its identity.

Where this leaves Fogo, in practical terms, is a clear set of improvements that naturally follow from the attacker’s view. Congestion should become a condition the network handles with predictable economics rather than panic behavior, which means scarcity should be priced under load and priority should be meaningful without becoming an attacker’s tool. Contention hotspots should be treated as normal and expected, which means the chain’s behavior under hot-account patterns should be measured, communicated, and improved so that the blast radius stays localized rather than spreading across user experience. Access should be treated as part of the product, which means redundancy and stability at the edge should be designed to survive bursts and malicious pressure without turning the network’s public face into its weakest point. Finally, all of this should be made visible through consistent measurement, because the fastest way to turn “performance claims” into “earned trust” is to show how the chain behaves on its worst days and how those worst days improve over time.